Apr 1: Russian leaders & their love of art and reputation washing

Articles by Valdyslav Vliasuk, Josh Rudolph and Casey Michel; posts- MacKay

Valdyslav Vliasuk, Putin and his allies love buying art. To help us win the war in Ukraine, confiscate it- The Guardian

Paintings and sculptures are easier to transport and hide than yachts and private jets. Don’t let them slip through the net.

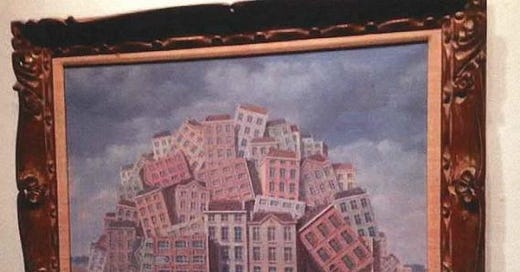

René Magritte, one of Belgium’s most famous artists, was a leading member of the 1920s movement called surrealism, which sought revolution against the constraints of the rational mind. When describing his paintings, Magritte said they “evoke mystery” and strived to ask beholders: “What does that mean? It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing, it is unknowable.” I sometimes feel as if I am looking at a Magritte painting when examining Russians’ ability to evade western sanctions policies.

Arkady Rotenberg, worth a reported $3.5bn (£2.9bn), is a childhood friend of Vladimir Putin. He used to be the Russian president’s judo sparring partner, before progressing to become a rich businessman. Rotenberg has publicly claimed to own the $1bn so-called “Putin’s Palace”, a huge Italianate complex on the Black Sea coast said to be secretly owned by the Russian president.

In March 2014, Rotenberg was one of the first Russians to be hit with sanctions after Russia unlawfully invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea. Yet two months after the restrictions were imposed, a complex web of shell companies linked to Rotenberg and his family was used to buy Magritte’s La Poitrine for $7.5m at a Sotheby’s auction in New York.

According to a US Senate investigation, the painting was shipped to a storage facility in Germany called Hasenkamp where it rested for five years. In August 2019, when the committee started investigating the purchase, the artwork was whisked off to Moscow. In its report, the congressional committee said the lack of banking regulations over art transactions was “shocking” and created an “environment ripe for laundering money and evading sanctions”. It directed sharp criticism at auction houses and art dealers for doing little to screen or stop sanctioned people from trading art.

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year, some additional measures have been taken. The auction houses Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bonhams cancelled sales of Russian art in London in response to western sanctions on the Kremlin and its wealthy cronies. But so much more could be done to tackle a notoriously opaque market which has been long favoured by Russian oligarchs looking to shift money around. After all, paintings and sculptures are easier to transport and hide than yachts and private jets, many of which have been seized over the last year. Art also provides oligarchs with a mechanism to launder their reputations – weaving themselves into such a gilded world provides cultural, social and political standing.

The arrival of the Russian super-rich in the art world was announced in May 2008 when Roman Abramovich, the then owner of Chelsea football club, bought Lucian Freud’s Benefits Supervisor Sleeping for £17m at Christie’s in New York. The next evening, he bought Francis Bacon’s Triptych for £43m from Sotheby’s. This largesse came one week after Putin flipped from Russian president to prime minister, extending his power beyond the two consecutive terms allowed under the constitution.

Leonid Mikhelson is the major shareholder in Novatek, a Russian gas company, and has done business with Gennady Timchenko, an oligarch who has been close to the Russian president for decades. Mikhelson was one of several oligarchs summoned to the Kremlin the day after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine last year. He has been sanctioned since 2014. Yet during the same time period, Mikhelson’s foundation has also had a presence in London’s public art institutions, staging four shows at the Whitechapel Gallery between 2014 and 2018.

Western allies of Ukraine seeking to put pressure on the Kremlin over the war crimes extravaganza unleashed on Ukraine could ban sanctioned Russians from their prestigious art markets, including auction houses. More stringent regulations about beneficial ownership could be introduced, which would help to clean up the real estate market as well as the art world. An international taskforce should be established to recover priceless works of art looted from Ukrainian galleries and museums by Russian occupiers. And western authorities should confiscate pieces bought by sanctioned individuals and their proxies. The money should go towards the reconstruction of Ukraine.

The UK will not have to look far for such items. Two months after the war started last year, its authorities could have made a real statement. The Victoria and Albert Museum hosted a blockbuster Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution exhibition displaying objet d’arts that the Russian jeweller sold to the British royal family and aristocracy at the beginning of the last century. In prized place was the Rothschild Fabergé clock egg from 1902, which includes a diamond-set cockerel popping out of the top every hour. The Rothschild egg had been bought at Christie’s in London in 2007 for £9m by Russian businessman Alexander Ivanov. It was transferred to the V&A exhibition by Ivanov’s Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg after receiving assurances from the UK that it would be exempt from seizure by the courts.

The egg was eventually returned to Russia months after Putin ordered his troops into a conflict in Ukraine that is increasingly defined by the deliberate targeting of civilians – in complete breach of all international laws.

Last week, the international criminal court in The Hague indicted Putin for the mass abduction of Ukrainian children and issued a warrant for his arrest. Given the current situation, it is unlikely that Putin will ever risk visiting a country that would honour the arrest warrant.

But another measure might have been taken to show the Russian president that the west means business. Some time after Ivanov bought the Rothschild Fabergé clock egg, he surprisingly decided to give it away. The ownership was transferred in 2015 to a Russian individual who was hit by UK, EU and US sanctions last year as Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine. His name is Vladimir Putin.

Vladyslav Vlasiuk is a sanctions expert working in the Ukrainian presidential office

Further reading

Josh Rudolph, How Art Dealers, Real Estate Agents, and Hedge Funds Enable Corruption- Foreign Policy

If Biden is serious about fighting corruption, he needs to regulate 10 key white-collar professions.

The FBI has long viewed obscure private investment funds as dangerous financial pathways for malevolent foreign activities. Nearly a decade ago, the bureau caught Moscow trying to use venture capital funds in Boston and Silicon Valley to steal U.S. military secrets. Last year, a leaked FBI intelligence bulletin warned about cryptocurrency scammers, drug cartels, and Russian organized crime increasingly using loosely regulated investment vehicles for crime and corruption in the United States.

The same FBI leak also pointed to the threat of foreign governments using investment funds for political influence operations. Russia and the United Arab Emirates allegedly tried to influence the Trump administration’s foreign policies through investment fund managers who were friends with then-President Donald Trump and his family, including by dangling lucrative deals before them.

Private investment companies such as hedge funds and private equity firms are only one sector among 10 types of white-collar professions whose loose rules pose grave dangers to US national security, as I've detailed in a new research report. Others are real estate title insurers, company formation agents, art dealers, lawyers, accountants, covert public relations firms, real estate agents, luxury car sellers, and cryptocurrency businesses. Highly nontransparent and insufficiently regulated, these financial professions have a long record of being used by hostile regimes and their cronies to weaponize corruption, launder funds, or skirt sanctions. For US President Joe Biden to advance the anti-corruption agenda he has announced, he needs to ensure that the US Treasury Department makes these professional enablers watch out for dirty money in the same way commercial banks are already required to do. [continue reading]

Casey Michel, How Russia’s Oligarchs Laundered Their Reputations in the West- The Intelligencer

Sanctions haven’t touched their face-saving philanthropy.

Following Moscow’s horrific invasion of Ukraine, an overdue wave of attention has been focused on where Russian and post-Soviet oligarchs hide their wealth in the West — from real estate to private equity to the art market. Until the past few weeks, however, less attention had been paid to how these oligarchs launder their reputations (in addition to their illicit assets) and gain access to the highest rungs of western policy-makers in the process.

This phenomenon of “reputation laundering” is hardly novel nor is it limited to oligarchs who made their wealth in the post-Soviet scramble for assets — using their connections to rising despots and organized crime to build portfolios worth billions. Nor is scrutiny or concerns about how nonprofits willingly accept tainted funds — and transform donors from oligarchs to “moguls” or “philanthropists” — limited to oligarchs close to Russian despot Vladimir Putin (see the Sackler family’s donations).

But over the past few years, the massive scale of donations made by oligarchs who emerged following the Soviet collapse has started to become clear — as well as what that has meant for western policy regarding the Kremlin and Moscow’s interference operations more broadly. Two years ago, as part of the Anti-Corruption Data Collective, George Washington University professor David Szakonyi and I created an initial database of oligarchic donations to more than 200 of the most prestigious nonprofits in the U.S. — from museums to universities to think tanks. Recipients included some of the country’s foremost institutions, such as Harvard University, the Brookings Institution, and New York’s Museum of Modern Art. As we found, oligarchs had donated anywhere between $372 million and $435 million to these nonprofits. (Because some donation disclosures provide only a monetary range in which the donation fell, our final number is likewise a range.) [continue reading]