Apr 11: Benjamin Berell Ferencz's legacy

Posts and articles on the life of Benjamin B. Ferencz from the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence, CNN and The New York Times

Benjamin Berell Ferencz

Benjamin Ferencz, a Nuremberg Tribunal prosecutor, died on April 7 at the age of 103. In 1947-48 he was a prosecutor at the trial of Einsatzgruppen which committed mass murders of civilians in occupied territories. He publicly condemned russia for its crimes in Ukraine:

"The crimes now being committed against Ukraine by russia are a disgrace to human society,those responsible should be held accountable for aggression,crimes against humanity and plain murder. As soon as they start dragging the criminals before a court the happier we will be."

Christiane Amanpour: “An extraordinary life lived in pursuit of justice. I was privileged to speak with Benjamin Ferencz last year, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “I am not discouraged,” he said. “I say never give up, never give up, never give up.”

Benjamin B. Ferencz, Last Surviving Nuremberg Prosecutor, Dies at 103

By Robert D. McFadden, The New York Times, April 8, 2023

In addition to convicting prominent Nazi war criminals, he crusaded for an international criminal court and for laws to end wars of aggression.

Benjamin B. Ferencz, the last surviving prosecutor of the Nuremberg trials, who convicted Nazi war criminals of organizing the murder of a million people and German industrialists of using slave labor from concentration camps to build Hitler’s war machine, died on Friday at an assisted living facility in Boynton Beach, Fla. He was 103.

His son, Don, confirmed the death.

A Harvard-educated New York lawyer whose concept of evil was formed when he was a Jewish soldier in Europe and a war-crimes investigator at Buchenwald, Mauthausen and Dachau, Mr. Ferencz (pronounced fer-RENZ) campaigned after World War II for restitution of property seized by the Nazis. For much of his life he crusaded for an international criminal court, and for laws to end wars of aggression.

The author of nine books and scores of articles, he was fluent in French, Spanish, German, Hungarian and Yiddish and spoke at world peace conferences. He was also widely quoted in interviews and wrote countless letters to editors.

His dream of a tribunal to prosecute war crimes was partly realized in 2002 with the establishment of the International Criminal Court in The Hague. But its effectiveness has been limited, and many nations, including the United States, do not recognize its authority.

Born to illiterate parents in Transylvania, raised in the Hell’s Kitchen area of Manhattan and plucked from obscurity as an Army corporal because he had researched war crimes for a professor, Mr. Ferencz was sent to newly liberated concentration camps by Gen. George S. Patton in the closing stages of the war and rose to prominence as the youngest prosecutor at the postwar Nuremberg trials.

Fulfilling an Allied pledge to bring war criminals to justice, 13 trials were held in Nuremberg, where Nazi rallies had celebrated Hitler’s rise to power in the 1930s. In the first and most important trial, held in 1945 and 1946, the International Military Tribunal convicted 24 of the Third Reich’s senior leaders, including Hermann Göring, Hitler’s designated successor, who committed suicide on the eve of his execution, and the military commander Wilhelm Keitel, who was hanged. The chief prosecutor was Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson of the United States Supreme Court.

A dozen subsequent trials at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg put German judges, doctors, industrialists, diplomats and less senior military leaders in the dock in cases supervised by Justice Jackson’s successor, Gen. Telford Taylor. Mr. Ferencz was assigned to prosecute the notorious Einsatzgruppen case, which for its staggering volume of victims has been called the biggest murder trial in history.

It was the case against 22 Nazis, including six generals, who organized, directed and often joined roaming SS extermination squads — 3,000 killers, aided by the local police and other authorities, who rounded up and slaughtered a million specifically targeted people, or groups, in Nazi-occupied lands: the intelligentsia of every nation, political and cultural leaders, members of the nobility, clergy, teachers, Jews, Gypsies and other “undesirables.” Most were shot, others gassed in mobile vans.

They were crimes that beggar the imagination — 33,771 men, women and children shot or buried alive in the ravine near Kyiv called Babi Yar; the two-day liquidation of 25,000 Latvian Jews from Riga’s ghetto, forced to lie down in pits and shot; the spectacle of a barbarian in Lithuania who killed Jews with a crowbar while crowds cheered and an accordion played marches and anthems.

Unfolding in 1947 and 1948, the Einsatzgruppen trial was Mr. Ferencz’s first court case. But the evidence — mostly detailed records of killings kept by the Nazis themselves — was overwhelming and irrefutable.

“In this case, the defendants are not charged with sitting in an office hundreds of miles away from the slaughter,” the court said in a unanimous judgment. “These men were in the field actively superintending, controlling, directing and taking an active part in the bloody harvest.”

All the defendants were convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Fourteen were sentenced to death and two to life in prison. Only four executions were ultimately carried out, however, which was typical of the Nuremberg trials: convictions, heavy sentences and later commutations. Analysts said leniency arose because the new realities of the Cold War with the Soviet Union meant that the Western powers needed Germany politically.

Mr. Ferencz, who was General Taylor’s manager for all the trials, was also a special counsel in prosecuting the Krupp trial, one of three proceedings against German industrialists. A dozen directors of the Krupp company, including the owner, Alfried Krupp, were accused of enabling the Nazis to wage aggressive war by manufacturing armaments, and of working slave labor, mostly Jews from Auschwitz, to death.

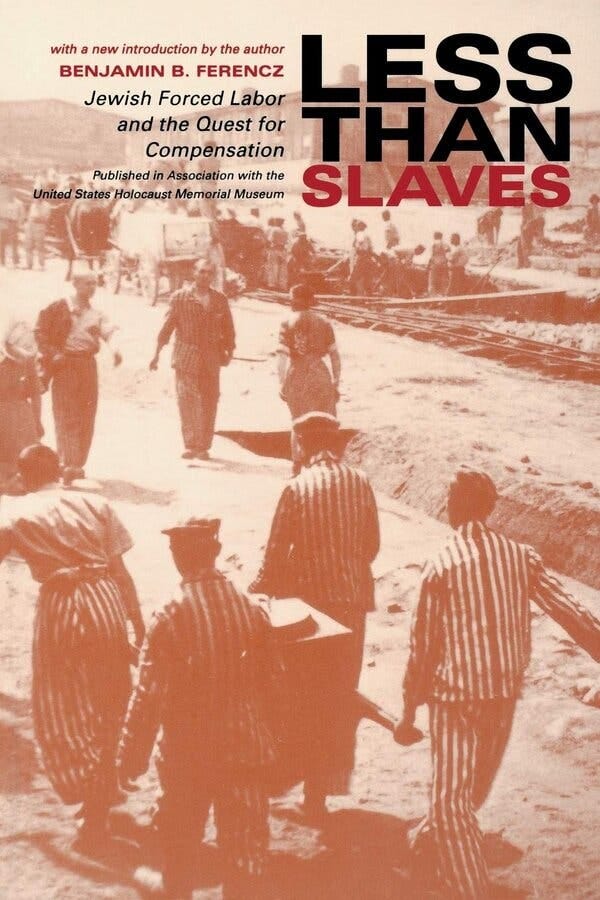

“The corporate directors were surprised and indignant to find themselves in the criminal dock,” Mr. Ferencz wrote in his book “Less Than Slaves: Jewish Forced Labor and the Quest for Compensation” (1979), on the refusal of I.G. Farben, Krupp and other companies to offer more than token postwar compensation to surviving victims.

“As far as they were concerned,” he continued, “the use of slaves was a patriotic duty which was both normal and proper under the circumstances.”

But the trial evidence clearly showed that Krupp flourished under the Nazis, and that it worked 100,000 slave laborers under brutal conditions that made “labor and death almost synonymous,” the court said in 1948 as it found 11 defendants guilty and sentenced them to prison terms of three to 12 years.

By 1951 all had been released, and by 1953 Alfried Krupp had resumed control of his company.

After the Nuremberg trials ended, in 1949, Mr. Ferencz remained in West Germany and helped Jewish groups negotiate a reparations settlement in 1952 under which West Germany agreed to pay $822 million to Israel and to groups representing survivors of Nazi persecution as what Mr. Ferencz and other critics called token compensation for suffering and for assets seized illegally. Only $125 million of the compensation went to victims; Farben, for example, gave only $825 per victim for years of horrific persecutions.

In 1956, he returned to New York and became General Taylor’s law partner. But in the late 1960s and early ’70s, as the United States became more deeply involved in the Vietnam War, Mr. Ferencz gradually withdrew from private law practice to write books and to promote world peace and a permanent international criminal court.

“Nuremberg taught me that creating a world of tolerance and compassion would be a long and arduous task,” he recalled on his website. “And I also learned that if we did not devote ourselves to developing effective world law, the same cruel mentality that made the Holocaust possible might one day destroy the entire human race.”

Benjamin Berell Ferencz was born in a thatched house in the Transylvanian village of Somcuta Mare, Romania, on March 11, 1920, to Joseph and Sarah Legman (Schwartz) Ferencz. In the shifting borders of the era, his sister had been born a Hungarian in the same house a year and a half earlier. When Ben was an infant, the family fled to the United States to escape a pogrom of Jews after Transylvania was ceded by Hungary to Romania under the 1920 Treaty of Trianon.

“We came here as poor immigrants,” Mr. Ferencz told The New York Times in 2000. “My parents were illiterate. No skills, no nothing, except two little children. I was raised in New York, Hell’s Kitchen, a high-density crime area. I recognized early that I wanted to do crime prevention. I was interested in juvenile delinquency primarily because I was surrounded by juvenile delinquents.”

He attended Townsend Harris High School in Manhattan, but he got into a spat with a dean over his refusal to attend gym classes and did not receive a diploma. He graduated with high honors from the tuition-free City College in 1940 and received a scholarship to Harvard Law School, where he studied under the renowned legal scholar Roscoe Pound. His research for Sheldon Glueck, a Harvard professor who was writing a book on war crimes, took him deep into the subject and proved critical to his career in Europe.

After earning his law degree in 1943, he enlisted in the wartime Army and became a private in an antiaircraft artillery unit. He joined the Normandy invasion in 1944 and fought across France and Germany. In 1945, his legal training and war-crimes expertise were recognized by the Army, and he was assigned to General Patton’s Third Army headquarters and then to investigate newly liberated concentration camps for evidence of war crimes.

What he witnessed was seared into memory. At Buchenwald, he said, “I saw crematoria still going. The bodies starved, lying dying, on the ground. I’ve seen the horrors of war more than can be adequately described.”

At Mauthausen, he found incriminating ledgers kept by the Nazi commandant on the number and manner of prisoners killed each day, on starvation rations and on horrific conditions in the lice-infested barracks. Sergeant Ferencz mustered out of the Army in Germany late in 1945.

In 1946, he married Gertrude Fried in New York. The couple soon returned to Germany, and their four children were all born in Nuremberg. His wife died in 2019. In addition to his son, he is survived by three daughters, Nina Dale, Robin Ferencz-Kotfica and Keri Ferencz, and three grandchildren.

Mr. Ferencz, who lived in New Rochelle, N.Y., and in recent years in Delray Beach, Fla., with his son Donald, taught at Pace University in Pleasantville, N.Y., from 1985 to 1996. In 2016, he gave $1 million and pledged millions more to the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington for its Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide.

His other books included “Defining International Aggression: The Search for World Peace” (1975) and “An International Criminal Court: A Step Toward World Peace” (1980). He was the subject of a 2019 documentary directed by Barry Avrich, “Prosecuting Evil: The Extraordinary World of Ben Ferencz.”

Although Mr. Ferencz supported the International Criminal Court, it fell short of his hopes. While it may prosecute genocide and war crimes under a treaty signed by more than 120 nations, its reach does not include wars of aggression, whose definition is elusive. Some 40 countries, including the United States, Russia, China, Israel and Iraq, did not sign or ratify the treaty. Critics say the court has focused on prosecutions in Africa while American wars have not even been investigated.

“The United States was in fact the leader in creating the rule of law in connection with war at the Nuremberg tribunals and inspired the world,” Mr. Ferencz told The Times, “and the president of the United States under our Constitution is vested with the sole authority to negotiate and sign treaties. But the authority seems to have slipped away.”

Robert D. McFadden is a senior writer on the Obituaries desk and the winner of the 1996 Pulitzer Prize for spot news reporting. He joined The Times in May 1961 and is also the co-author of two books.