Apr 19: Lara Dihmis, What’s in a Name? Searching for People Across the Border

As published by the OCCRP Team on April 12, 2023

What’s in a Name? Searching for People Across the Border

By Lara Dihmis, the OCCRP Team, April 12, 2023

As OCCRP’s follow-the-money reporting shows, it’s increasingly common for criminals to have foreign associates — business partners, proxies or even a significant other — who facilitate their cross-border operations.

That’s why, for us on the research team, investigating such figures almost inevitably means going outside the comfort zone of our regional expertise.

Sometimes this means having to learn how to access company registries in countries that are new to us. (Luckily, we have this handy catalogue to help.)

But it can also mean having to identify and investigate people whose names use different alphabets, are formed by unfamiliar conventions, or carry unexpected cultural signals.

In this post, we’d like to share some best practices on how to investigate names from outside the English-speaking world.

Naming customs vary widely, so we can’t cover everything. But the below examples should help researchers find a way forward when faced with an unfamiliar name.

What a Name Can Reveal

Some names can reveal a surprising amount of valuable information about a person’s gender, ethnicity, marital status, and more. You just need to know what naming conventions to look for.

In Western culture, the father’s surname, which is usually passed down, is often the only clue we can draw on when trying to map out other relatives.

This makes finding other family members more difficult, and means having to get creative. For example, one investigation required us to prove that a Canadian man who held a luxury property portfolio on behalf of the chairman of a major Russian bank had a son who had worked at that bank for years. To confirm this relationship, we used social media posts to find pictures of the father-son duo together.

In many other cultures, such as in various Arabic-speaking and Balkan countries, Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, and some regions of Southern India and Sri Lanka, names can reveal more. Middle names are composed of either the father’s, or both father’s and grandfather’s names, and if the first name is ambiguous, you can determine gender based on other identifiers.

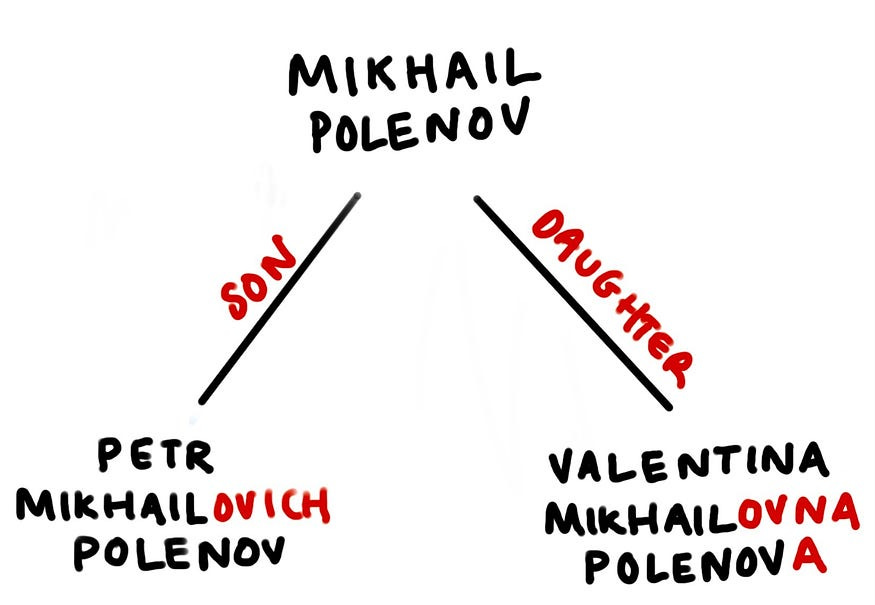

In Russia, for example, the middle name — called the “patronymic” — is derived from a person’s father’s name, but it’s not his full name, and it varies based on gender. If the individual you’re looking at is a male, his patronymic will consist of his father’s name, plus “vich.” A woman’s middle name will be her father’s name plus “vna.” Female surnames usually have an additional “a” at the end.

For example, the son of Mikhail Polenov could be Petr Mikhailovich Polenov, while his daughter could be Valentina Mikhailovna Polenova.

In other places, like North Macedonia, the middle name is the father’s exact name.

Knowing this can be extremely helpful, especially when trying to identify relatives. For example, last year, our North Macedonian partner was digging into the former head of the country’s secret police, Sašo Mijalkov, who was involved in a major corruption scandal and imprisoned for abuse of power.

Among their findings were some luxury local properties in the name of a person named Jordan Mijalkov.

While reporters knew Saso had a son called Jordan, his father also had the same name. Which one was he? Some extra digging eventually revealed his full name, Jordan Sašo Mijalkov, confirming that the properties were in the name of the official’s son.

In the Middle East and North Africa, names can be even more revealing, yielding not only the name of a person’s father but also their grandfather.

Just by looking at the name Hafez Bashar Hafez Al-Assad, for example, you can conclude that his father’s name is Bashar Hafez Al-Assad and his grandfather’s name is Hafez Al-Assad.

In some cases, you can also learn the name of someone’s eldest son through their nickname. For example, Saddam Hussein also went by “Abu Uday,” or “Father of Uday,” after his infamous eldest son.

In most parts of East Asia (and some other places, like Hungary), it’s important to know that surnames usually go before first names, and there’s rarely a middle name.

For example, “Xi” is the surname, not the first name, of Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

But these names can trick you twice! It’s important to know that people of East Asian descent often use the conventional Western order — first name first — on foreign company or property records. To make sure you find them, you need to try both versions..

For example, the Vietnamese-American author Viet Thanh Nguyen is an American citizen, so his name is structured in the ‘western’ way. In Vietnam, his name is Nguyễn Thanh Việt.

These elements are important to note, especially when you’re trying to identify relatives to verify an individual (something we’re often tasked with doing in the fact-checking process).

Lost in Transliteration

If you’re trying to identify a person whose name uses a different alphabet, and only have the spelling in Latin characters, you might be tempted to auto-translate it into their language before you do an internet search.

For example, if you have corporate documents from Israel, but the shareholders’ names are written in Hebrew, you can pop them into a free translation tool (such as Google Translate or Reverso Context), and get the name in Latin characters.

This is a useful method, and often gets you at least some kind of result. But it’s important to note that if someone’s name means something, these tools don’t always stick to just transliteration. Often, they’ll translate the name instead.

For example “Ward” (“ورد”) is a common name in Arabic. But it also means “rose” or “flower,” and that’s what an automatic translator will usually give you. Conversely, if you translate the name into Arabic using Latin letters (“Ward”), it would give you the Arabic meaning of “ward” (as in, hospital ward).

There are many such cases. In Hebrew, Adi (“עֲדִי”) is a common name, but it also means “jewel.” In Chinese “远” (“Yuan”), another common name, will likely translate to “far.”

[Read more about how OCCRP’s Aleph processes ‘synonames’ and transliterated text here.]

Many names also have seemingly endless variations.

The most obvious example is “Mohammad,” one of the most common names in the world. It can be written as “Mohamad,” “Mohammed,” “Mohamed,” “Muhammed,” “Muhamed,” “Muhammad,” and so on.

Sometimes additional variations arise when letters in non-Latin alphabets can be transliterated in different ways.

For example, depending on the language, the letter “Š” can be written as “sch” or “sh.” The same goes for “Č,” which can be a “tsch” or a “ch,” and “Ć,” which is pronounced “tj” but is sometimes written as “c.”

The Cyrillic letter “Ч” — found in the name “Трајче” — can be written as “c” or “ch.” So, when searching, you’d want to try “Trajche” or “Trajce.”

And in Russian, the letter “Ë” is pronounced “yo” but usually written simply as E, obscuring the difference to non-native speakers. So, while a spelling like “Gorbachev” tends to be more common in English, a transliteration that preserved the original pronunciation would look like “Gorbachyov,” and might be used by some people.

When faced with such names, it’s important to try as many reasonable variations as you can think of, because you never know what you might find.

For example, when OCCRP/KRIK reporter Dragana Peco began digging into Belgrade’s former mayor, Šinisa Mali, she ran her first batch of searches using the Serbian spelling. But since there’s no “Š” in English, she thought that he might use a different spelling if he has any foreign properties or companies.

Knowing that “Š” is pronounced “sh,” but might also be written as “S” when transliterated, she tried searches using both “Sinisa” and “Sinisha.” Through the latter variation, she was able to identify his association with two companies registered in the British Virgin Islands. This led to an investigation which uncovered that he secretly purchased, through offshore companies, 24 resort apartments on the Black Sea that were worth over $6 million.

There are dozens more examples from other alphabets and dialects.

In China, for example, Wang (“王”), an extremely common surname, is pronounced “Wang” in Mandarin, “Wong” in Cantonese, “Ong” in Hokkien, and “Heng” in Teochew, and therefore may be written in any of these ways. The same goes for Chen (“陈”), another common Chinese surname, that’s usually pronounced “Chan” or “Chun” in Cantonese, “Chin” in Hokkien, and “Tang” in Teochew.

So while there are a number of variables to consider, and endless variations to try, spending the time thinking through or even writing down all of the variations you can think of before embarking on your searches will likely help you get better results.

No one is proficient in every language, and even seasoned researchers often come across names that challenge them. Hopefully, this blog post can help convey an idea of what kind of factors to consider when investigating interesting foreign characters.