Apr 2: Soldatov & Bogodan, China Finally Enters Russia’s Technological Treasure House

As published on the CEPA website on March

Andrei Soldatov & Irina Bogodan, China Finally Enters Russia’s Technological Treasure House, CEPA

Little-noticed developments indicate that China’s long march to enter Russia’s top scientific faculties has succeeded.

While Vladimir Putin was busy courting Xi Jinping in the Kremlin, prompting many to ask whether their cooperation was extending to weapons shipments, a more strategic shift between China and Russia was emerging.

In March, so many Russians applied for Chinese visas that the two-month allotment was exhausted in as many days. The huge demand was prompted partly by tourists eager to see China now that lockdown restrictions have been lifted, but the stampede also involved businesspeople desperate to address the technology and equipment famines caused by the all-out invasion of Ukraine and the consequential storm of sanctions. Many visa applicants were from Russian telecoms and IT companies hoping to attend the Canton fair in Guangzhou in April.

It, therefore, came as little surprise that one of the agreements signed by Putin and Xi concerned cooperation in information technology and the digital economy. Unstated, but clear to anyone following Russian-Chinese relations, the deal signified significant concessions and strengthened the argument that the Kremlin is now playing little brother to Xi’s regime. This was a breakthrough the Chinese had aspired to for decades.

It is true that technological cooperation was uninterrupted by the war. While the communications giant, Huawei, shut its enterprise division in Russia, the telecom giant maintains research and development centers in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Nizhny Novgorod, and Novosibirsk, including the Huawei Research Institute, which has been hiring new researchers throughout the first year of the war.

But of much greater interest to China is access to Russian technological research and development programs, the same programs its scientists have feasted on in the US.

In the 1970s, the Carter administration, eager to normalize diplomatic relations through educational exchanges, offered places for Chinese students in the US.

The Chinese leaped at the opportunity, and instead of the few hundred expected by the State Department, China asked for as many slots for its students as all other countries combined — dozens of thousands arrived, according to Daniel Golden’s 2017 phenomenal book Spy Schools: How the CIA, FBI, and Foreign Intelligence Secretly Exploit America’s Universities. This was only the start.

While US college graduates with a flair for engineering or computer science join high-tech companies or launch startups, it is the international students, many of them from China, who came to dominate graduate programs in those fields at US universities, providing the workforce for American cutting-edge research.

Russia never allowed Chinese students this kind of access – paranoia on both sides prevented full cooperation in technical education.

China sent its first students to Russia in September 1948, to study engineering and medicine. Many attended the Bauman engineering school in Moscow, on the Yauza river, now Bauman Moscow State Technical University. It is the best engineering university in the country, which has been heavily involved in military and security research – from missiles and tanks to surveillance technologies. Andrei Bykov, deputy head of the FSB in the 1990s and father of the Russian national telecom surveillance project SORM, is a graduate.

But this rosy period of cooperation ended abruptly in 1962 following the worsening of relations between the two countries. Chinese students only began to return in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Once again, they focused on Bauman, an effort promoted by a Chinese statesman Song Jian, the father of the first Chinese submarine-launched ballistic missile, the JL-1. A Bauman graduate, Song Jian was an honorary chairman of the society of Chinese graduates of Bauman University in the 1990s and the president of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, but most importantly, he headed the State Science and Technology Commission — the main government body coordinating science and technology in China.

Bauman University welcomed Chinese students, but not in big numbers, and none stayed to do research, unlike at US universities.

In the 2000s, the atmosphere worsened as Russia’s research community was struck by spy mania and subjected to a ruthless FSB campaign. Interestingly, these were not just aimed at those allegedly spying for the West. Those jailed on FSB evidence included a number accused of sharing secrets with the Chinese.

The FSB mostly targeted research facilities, but in 2016 it was Bauman University’s turn when a rocket scientist and professor at the institution, Vladimir Lapygin, was jailed on charges of spying for the Chinese. The 76-year-old professor was sentenced to seven years in the strict regime of a prison colony. Needless to say, this put a chill on scientific and research cooperation.

The Chinese kept trying. Apparently realizing that they would never get access to Russian engineering schools on the scale they wanted, they changed the strategy. China began asking Russia to open local branches of its technical universities. Once there, students would have unrestricted access to the Russian professors, far from the watchful eye of the FSB.

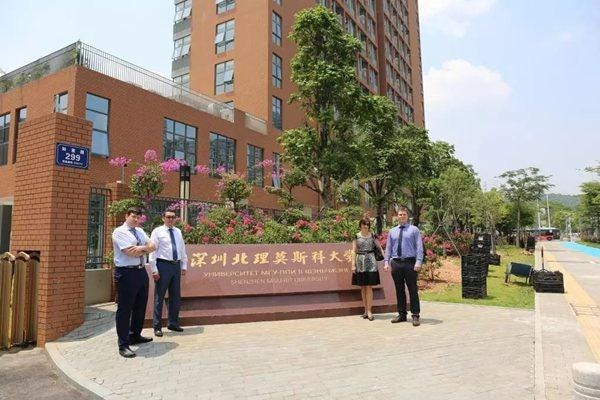

From 2014 China was to launch a Russian-Chinese university in Shenzhen, and in 2017 it eventually got its campus and first students. But, once again, the Russians were playing games.

The Russian-Chinese university in Shenzhen is a joint venture: China is represented by the Beijing Institute of Technology and Russia by Moscow State University (MSU); as a nod to the Russians, the main building is modeled after the famous MSU high-rise. But MSU doesn’t teach engineers. Instead, it opened a Russian language center and programs on biotech. Back in Russia, there were still fewer than 40,000 Chinese students overall, and most of them were likewise studying Russian, not engineering.

In 2019, the Chinese achieved a breakthrough – Harbin polytechnic launched a Bauman engineering institute in Harbin, a joint project with the eponymous university.

Still, it was a relatively small effort, and not everybody welcomed a joint venture. “Hmm, some might think it unwise to transfer such knowledge. Leaks can happen via this institute. It is better to build non-engineering universities,” was one comment below the news about the project.

Only when Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine was the decisive step taken. In July, Bauman agreed to participate in the joint venture in Shenzhen. “We decided to . . . establish cooperation with Bauman University so that students, as was planned, would study according to the highest Russian standards,” explained Sergei Shakhrai, Vice President of Moscow State University in Shenzhen.

It took a war to make it happen, but China has got its way. Last week an ad for Chinese language courses for students popped up on the Bauman University website.

Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, both non-resident senior fellows at CEPA, are Russian investigative journalists, co-founders, and editors of Agentura.ru, which monitors Russian secret service activities. Both have covered Russian security services and terrorism for more than two decades.