Feb 1: Janne M. Korhonen- Finland's Winter War and lessons learned to help Ukraine

Thread published on January 26, 2023

Janne M. Kornonen, Finland’s Winter War and the lessons learned to help Ukraine

How [does] the Western aid to Ukraine helps even outside the battlefield, and why the West should begin credible preparations to intervene directly?

Finland's Winter War (1939-40) provides an interesting historical case study of a somewhat comparable situation. Let's take a look!

Many have noticed the eerie parallels between the Winter War and Ukraine's struggle today. Like Putin, Stalin was convinced an invasion would be easy. And like Putin, Stalin committed massive forces once the defenders refused to budge.

And like Ukraine, Finland fought alone.

However, foreign aid and ‘offers of aid’ to Finland had a crucial impact.

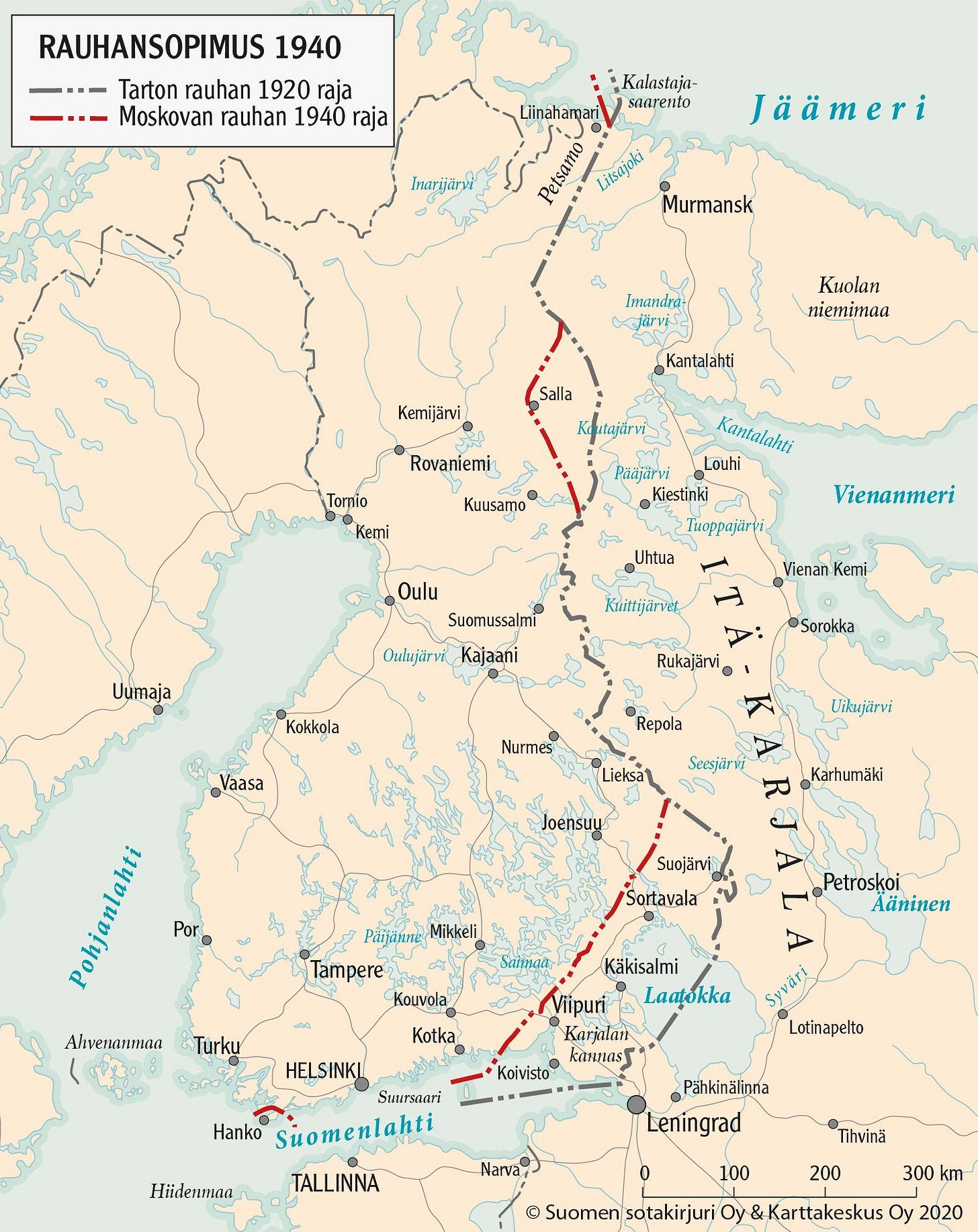

The war began after Finns had refused Stalin's demands that would have drawn Finland into the Soviet orbit, like the Baltic countries. Stalin's war aim was evidently a total conquest of such an upstart.

That Stalin sought to conquer and probably ultimately annex Finland is evidenced by operational plans and orders captured by Finns - some containing strict instructions on how the Red Army troops should greet the Swedish border guards - and the creation of a puppet government.

Once the war began on the 30th November 1939, the Soviet government refused to negotiate with the Finnish government. Instead, it considered Stalin's puppet government the "real" government of Finland. But on January 28, the Soviets suddenly signaled they were ready to negotiate. Why?

Because the Western Allies were coming.

France, in particular, was keen to send Allied forces to Finland through Norway and Sweden - and attack the Soviets from the south as well, for example, by bombing the oil fields at Baku.

The key reason: the Soviet Union was the key ally of Hitler. Under the umbrella of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, Hitler and Stalin had carved up Poland, and Soviet oil and raw materials supported the Nazi war machine. Stalin was now taking his share of the loot.

In September 1939, the French strategy had been based on the belief that a long war would favor the Allies. A blockade would weaken Germany while the Allies built up their militaries. But Soviet aid, in particular, and iron ore from northern Sweden, derailed the assumptions.

Furthermore, neutral European countries feared Germany. Like Belgium, they refused to commit to the side of democracy. The French wanted to show the Allies could help.

Hence, a plan to help Finland - and knock out Swedish iron ore in the process.

A very common assumption is that denying Swedish iron was THE reason why the Allies planned to send troops to northern Norway and Sweden. A Finnish historian Henrik Tala shows in his study that this is a half-truth at best. France especially really planned to help Finland. Tala's 2012 PhD thesis and 2014 book argue, convincingly in my opinion, that the French government was "almost manically" committed to helping Finland. The reasons were of course partially self-serving, but the commitment to defend democracies shouldn't be discounted. Practical difficulties, indecisiveness, and the cooler British attitude were the key reasons the plan didn't materialize.

Finally, in early March 1940, the Allies were ready. The main force was to set sail on March 15. But on March 11, Finland sued for peace.

Yet the plan alone probably saved Finland. Tala argues that THE reason Stalin was willing to negotiate even though the Red Army was finally winning was that he really feared a war with the Allies. And the Finnish peace negotiators in Moscow understood this.

By March 1940, the Finnish army was at the end of its tether. Artillery ammunition, whose stocks had been alarmingly small from the beginning, was nearly exhausted. The last reserves had been committed. Troops fought without rest, and tired men suffered huge casualties.

When the Finnish government decided to accept the Soviet terms, the Finnish defenses may have been mere days and, at most, maybe two weeks from total collapse. The Western promises were too little, too late. But without them, Stalin wouldn't have had any reason to negotiate.

History doesn't repeat itself, but sometimes it rhymes.

I argue that democratic powers, including the EU, should begin credible preparations to directly intervene in Ukraine. Even if intervention never occurs, a credible threat would pressure Putin towards negotiations.

Calls for a negotiated end to the war are common and understandable. But as perceptive observers have noted, the Kremlin hasn't bothered to negotiate an end to any of its recent wars. It hasn't had a reason to do so.

Even widespread discussion of intervention would help. With adequate support, Ukraine could inflict such a defeat on the Russian military that Putin agrees to negotiate. But that is not certain, and it would mean a massive loss of life on both sides.

Whatever pressure we can add would lessen the slaughter. Pressuring only ‘Ukraine’ to negotiate, e.g. through threats to restrict aid, is not only morally repugnant. I don't believe it can end the war, only pause it.

The problem is not Ukraine. It's that Putin's reasons to negotiate are limited to a pause for rearmament. If democracies stepped up the pressure, mass troops, airpower, etc., and began public deliberations about direct intervention, the Kremlin couldn't discount the possibility entirely. They would probably conclude that the probability of intervention would increase over time. In other words, credible preparations to intervene would put Putin on a clock. Right now, he believes time favors Russia, and eventually, the West loses interest.

He may be right. He is absolutely right to assume that a long war would be very costly to the West as well. A speedy conclusion to the war would save lives and money on all sides. Credible preparations to intervene would certainly help.

Forces massed for intervention would also be ready to respond to other contingencies, increasing the range of policy options. Credible preparations for intervention would also show that democracies are serious. It would be a stern warning to all autocrats. Maybe it could help break the historical pattern of autocrats underestimating the democratic resolve and then starting wars against democracies.

Preparations to intervene, even if no intervention actually materializes, are of course both costly and incur some risk of escalation. I don't believe the risk is large, however: it is already very clear that Russia isn't willing to go to war against NATO.

The key source for the historical case study is Henrik Tala's excellent PhD thesis and the book it spawned, Talvisodan ranskalaiset ratkaisijat, which I think every Finn interested in security policy ought to read.

#CeterumCenseo, I believe Russia must lose. If Putin can outlast democracies by cynically driving barely trained reservists to slaughter, it would create a very bad precedent and increase the risk of even worse wars in the future.