“From Russia with Love”

Russia’s strategic goals in Italy and how it achieved them

Monique Camarra, Institute of World Politics, 26 Nov 2023

For over one hundred years, Russia’s strategic aims focused on advancing its aggressive foreign policy, and eroding the capacity of the United States and its allies to counter their activities. In order to achieve these aims, Russia employed non-kinetic warfare on both sides of the Atlantic. [1]

In Italy, Russia has been successful in advancing its foreign policy aims through the use of covert and overt active measures. This paper will discuss Russia’s aggressive strategic aims mainly after 2012, and how it succeeded in bringing Italian foreign policy in line with Russian positions in 2018, constituting a threat to the European Union (EU) and the NATO alliance. Russia implemented instruments of political, economic, and psychological warfare by working mainly through two parties—the League and the Five Star Movement—from 2012 to the present. The paper will conclude with a set of recommendations for decision-makers who wish to bolster Italian national security interests in the face of on-going Russian non-kinetic warfare.

Russia has always expressed interest in Italy owing to its strategic position in the Mediterranean, and because it considered Italy to be the “weak link” in the European Union and NATO. If Russia were to succeed in bringing Italy, a founding member of the European Union, to Russia’s foreign policy positions, it could undermine the EU, its institutions and policies. In doing so, it could deprive the United States and NATO of a strategic ally. That’s what Russia actively set out to do, slowly at first, and then aggressively after 2012. [2]

A Brief Overview of the Russian capture of the Italian intelligentsia and Business Elites

At the forefront of research into Russian operations in Italy, the Germani Institute in Rome has revealed that Russian hybrid warfare took on many forms over the past one hundred years, the most successful of which was the subversion of decision-makers and opinion-shapers through the tools of psychological and political warfare beginning in the Soviet era. [3]

The Italian Communist Party (PCI) became the Soviet Union’s main vector for Russian active measures in Italy. The party operated to shape Italian perceptions of the Soviet Union and the West for forty-five years, and brought a broad cross-section of Italians to Soviet positions on domestic and foreign policy. It did so through the strategy of cultural hegemony, devised by Antonio Gramsci, an Italian Marxist. A Bolshevik-style revolution in Italy was out of the question in the post-WWII era, but transforming Italian society from the inside, slowly and methodically, was possible. To this end, the PCI penetrated Italian cultural institutions, universities, the press, television, publishers, entertainment, churches, unions, and associations to advance the Soviet ideological revolution through activities funded via the KGB and Soviet bloc agents. Their Italian agents of influence spread anti-American, anti-Western, and pro-Soviet propaganda, which was carried forward by the influential Italian Russlandversteher in the press, universities and think tanks to the present. [4]

Another crucial aspect of Soviet active measures in the 1970s and 1980s was the covert funding of subversive terrorist groups, and extreme-left and separatist movements. Documents from the former Soviet bloc archives reveal that the aim of the Red Brigades--the PCI’s armed faction—was to destabilise Italian society. The KGB tasked the Czech STB intelligence services to provide support for their covert operations.[5] In order to mask their activities, the Soviets released a false American army manual, alleging that the CIA was at the heart of the terrorist turbulence in Italy, feeding anti-American sentiments and distorting Italian perception of the West. [6]

The most significant period for the Russian capture of Italy’s financial and economic establishment occurred from mid-1980s to 2005. The Russians reactivated Russo-Italian economic, financial, and media networks in the mid-1980s. The most influential representatives of this time were Silvio Berlusconi, former prime minister of Italy and media mogul, and Antonio Fallico, president of Intesa Bank Russia and Conoscere Eurasia, founded in 2008 to promote economic, political and social ties with Russia. These figures had a significant impact on Italian foreign policy: they were part of a hidden Kremlin-aligned network of the establishment, operating off-shore shell companies and think tanks, which advanced Russian strategic aims. [7] Russian non-kinetic and kinetic attacks in Ukraine (2006), Estonia and Lithuania (2007), and Georgia (2008) did not serve to change their direction.

Unleashing the Nationalist-Populist Forces in Italy

The Kremlin believed that the United States and its allies were behind the protests that erupted in the Russian Federation in 2012. As a result, it went on the offensive between 2011 and 2013, implementing a “strategy of chaos.” Its aims were to undermine NATO and the EU, foment tensions among the Euro-Atlantic allies, encourage domestic polarisation and instability in the EU, and discredit liberal democracy. In addition to the traditional Soviet active measures, the Kremlin supported the growth of anti-establishment, nationalist-populist parties and extreme right and left movements in Italy and in the EU. [8]

The Kremlin looked to the League, headed by Matteo Salvini, and the Five Star Movement (M5S), headed by Beppe Grillo and Roberto Casaleggio, as well as far-right movements, Casapound and Forza Nuova to advance its strategic aims. The League and the M5S began to express pro-Russian views, and were aided by the Kremlin’s disinformation machine to disseminate them. In exchange, both received high-level political support from Russian authorities, and the Russian state media, which increased their visibility. [9] In terms of financial support, no evidence has emerged confirming Russian funding of the two parties. However, in 2018, “L’Espresso” released audios of a conversation between senior League representatives and Russian businessmen linked to the Kremlin. They were discussing a plan to funnel three million euro to the League through a scheme involving Rosneft and ENI, the Italian energy giant. The funds were supposed to cover the costs for the 2019 European parliamentary election. [10]

Russian hybrid operations out in the open: Success

According to Sergio Germani, one of Italy’s foremost experts on Russian hybrid warfare, over thirty significant instances have been documented concerning pro-Russian events and activities in Italy between 2013 and 2019. Beyond the purview of Germani’s analysis are two events in March 2020, and July 2022, which also indicate possible Russian interference. The following events and activities demonstrate evidence of Russian active measures at play in Italy in these crucial years.

The League’s transformation into a nationalist-populist party occurred in 2013 when Matteo Salvini was elected as its leader in the presence of senior Russian officials, Aleksey Komov (World Congress of Families, and St Basil the Great Foundation), and Viktor Zubarev (United Russia Party). Afterwards, Salvini also established ties with Russian ethno-nationalist intellectuals, including Aleksandr Dugin. [11] He and other neo-Eurasianists became mainstream figures in the Italian media due to the efforts of Salvini’s key policy advisor, Gianluca Savoini. In 2014, Savoini opened the Lombardy-Russia Cultural Association in order to develop political and business relationships with Russian politicians and elites, and disseminate Russian propaganda related to foreign policy issues. The oligarch, Aleksey Komov, became the association’s honorary president. [12]

The League and M5S openly advocated for Russian foreign policy positions through significant actions in the Italian parliament and in the EU. Leghisti acted as observers for Russia’s illegal referendum on the annexation of Crimea in 2014; they proposed a “roadmap for peace” along Russian lines, opened ‘consulates’ for the illegitimate Donetsk Republic, and advocated for removing sanctions against Russia. The League established a “Friends of Putin” parliamentary group, and signed an official protocol with the United Russia Party in 2017. [13]

In the summer 2015, Manlio di Stefano, M5S group leader at the Foreign Affairs Commission of the Chamber of Deputies, officially accused the West of turning Ukraine into a puppet of the United States, and a NATO base from which the West would launch an assault against Russia. In another conference that summer, in the presence of Aleksey Klimov, the deputy chairman of the Duma’s Foreign Affairs Commission, he advocated for closer relations with BRICS, an “economic alliance” with Russia, and the need for intelligence sharing between Italy and Russia. [14]

The Movement presented a radical bill to the Italian parliament to be put to a vote in 2017: it required Italy’s NATO membership to be reviewed every two years. There is no proof that the bill was drawn up by one of the M5S’s Russian contacts, but its presentation indicated that the M5S was ready to revolutionise Italian foreign policy. In the same year, M5S published its formal foreign policy document. It stressed that Italy’s national interests were incompatible with NATO, which needed “fundamental reforms, and called for the cessation of all Italian NATO missions. [15]

Before and after the Italian general election in 2018, the League and M5S benefited from the Kremlin’s media exposure on RT, RIA Novosti, Sputnik and Sputnik Italia. Just before the 2018 general election, Russian information campaigns amplified narratives to increase tensions: they created an image of Italy on the verge of chaos due to EU policies and politicians, who were unable to resolve the migrant crisis, which Russia had created. ‘Sovereigntism’ was the only solution. Italian outlets, such as Tze Tze and the Anti-Diplomatico, published Russian articles from RT and Sputnik, spreading Russian propaganda. Alto Data Analytics conducted an analysis of one million posts on social media and found that ten percent were stories published by Sputnik Italia, featuring the migration crisis narrative. [16]

The 2018 general election brought the Movement and the League to power. [17] They formed a ‘red-brown’ government, choosing an unknown lawyer, Giuseppe Conte, as their prime minister. The Russian establishment and elites were elated: Donald Trump was U.S. president, the United Kingdom had broken with the EU, and now Italy could be used as a launch pad for further Russian hybrid operations to weaken the EU and NATO. Putin anointed the Conte 1 government with an official visit on 4 July 2019. [18]

“From Russia with Love”: Italian and NATO security at risk

The League-M5S government lasted a little over a month afterwards due to internal squabbles. The resulting political crisis brought in a new coalition government--the Movement and the Democratic Party (PD)--under the continued leadership of pro-Kremlin, Giuseppe Conte. The PD Party would have no effect on Conte, who ‘invited’ the Russians back into Italian affairs. In doing so, he put Italian national and NATO security at risk.

On 22nd March 2020, Russian military vehicles made their way from Rome to Bergamo, brandishing Russian flags and signs bearing the slogan, “From Russia with Love”. Unbeknownst to the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defence, prime minister Conte had called Putin the day before, claiming that the EU had turned its back on Italy, and ‘needed’ Putin’s help. Within hours, fifteen II-76s military aircraft in Moscow were ready to transport 22 military vehicles, 120 military doctors, bacteriological warfare specialists, an analysis lab, 3 sanitisation units, 600 ventilators, 326,000 masks, and 1,000 protective suits. The operation was under the command of a high-profile authority, General Sergey Kikot, head Moscow’s bio-chemical warfare unit. The Russian Ministry of Defence’s media arm, Zvezda TV, filmed the event, which it amplified across Russian propaganda networks. [19]

Russian propaganda video.

Italian journalists and the Italian Parliamentary Intelligence Oversight Committee (COPASIR) later revealed that the operation was a Russian influence and intelligence gathering mission on NATO territory, funded entirely by the Italian government. Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, the former commander of the Uited Kingdom’s Joint Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Regiment, went on record to say that he was sure many Russian GRU agents had been sent to “discover as much as possible about the Italian forces, and establish an intelligence network.”. [20] When an Italian investigative journalist, Jacopo Iacoboni, reported on the operation, he was publicly bullied by General Igor Konashenkov. He warned him that, “He who digs the pit, falls into it”, a direct physical threat that got the attention of NATO, the Council of Europe and the EU. [21]

It is clear that Russia helped to instal a nationalist-populist government to advance its strategic goals. The Kremlin was successful in weakening Italy’s relationships with its traditional partners in the EU and NATO: Italy had been isolated in Brussels. Russian military personnel and GRU agents in Italy constituted a concrete breach in NATO and Italian security, consequences of which are still unknown today. As war raged in Ukraine in 2022, the League and M5S did the unthinkable: they brought down the Unity government for the benefit of Russia.

Russia’s number one enemy in Italy: Prime Minister Mario Draghi

Former European Bank president, Mario Draghi, was called to head a Unity government after the collapse of the Conte II coalition. He was asked to guide Italy through the pandemic storm, and restore its credibility internationally. Being a highly respected figure in the EU, Italy’s partners in Brussels and NATO were assured that Italy would return to the Euro-Atlantic fold. [22]

He moved quickly to address significant security concerns: his first act as prime minister was the arrest of Italian Naval officer, Captain Walter Biot, who was caught selling NATO documents to his Russian handler, Dmitry Ostroukhov. He and thirty GRU agents, operating as ‘diplomats’, were expelled immediately. Draghi also froze all contracts signed between Chinese and Italian companies, thought to threaten Italian strategic industries. [23]

When Russia unleashed its full-scale invasion against Ukraine in February 2022, Draghi reaffirmed Italy’s commitment to Ukraine, promising to provide armaments, ammunition and humanitarian aid in support of its “heroic” defence. Within weeks, he began to advocate for Ukraine’s accession to the EU, and an increase in sanctions against Russia. Within months, Italian authorities froze Russian assets, including Putin’s yacht, the Scheherazade. [24]

For Italians, Draghi’s competence was a source of pride: he had the highest approval rating amongst G7 leaders, which ranged anywhere between sixty-five to sixty-nine percent until late spring 2022. It fell precipitously to forty-eight percent in June 2022, signalling to many information warfare analysts that something was amiss. [25]

Russia matched the vigour of its ground assault in Ukraine to its hybrid warfare operations against Ukraine’s allies, Italy included. According to COPASIR, Russian hybrid warfare in Italy took the form of information attacks, energy pressures (which triggered inflation), and cyberattacks on public and private financial businesses, and state infrastructure as well as espionage. [26] Draghi and his cabinet introduced countermeasures to reduce Italy’s energy dependency on Russia by finding alternative energy sources, and enhanced the capabilities of the new cybersecurity unit to thwart attacks against state infrastructure and banking institutions. [27] However, Italy’s information space was still vulnerable to the deluge of Russian disinformation.

Recent investigations have emerged revealing that Russia may have orchestrated Draghi’s demise in order to eliminate a powerful voice in support of Ukraine. Heading the attack on Draghi in Italy were former prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, and Matteo Salvini. “The incredible thing is,” Italy’s foreign minister, Luigi di Maio, said, “this is a prime minister attacking Draghi, helping Putin’s propaganda and autocracy over democracy”. [28] The operation began where it would have the most effect: in the information domain.

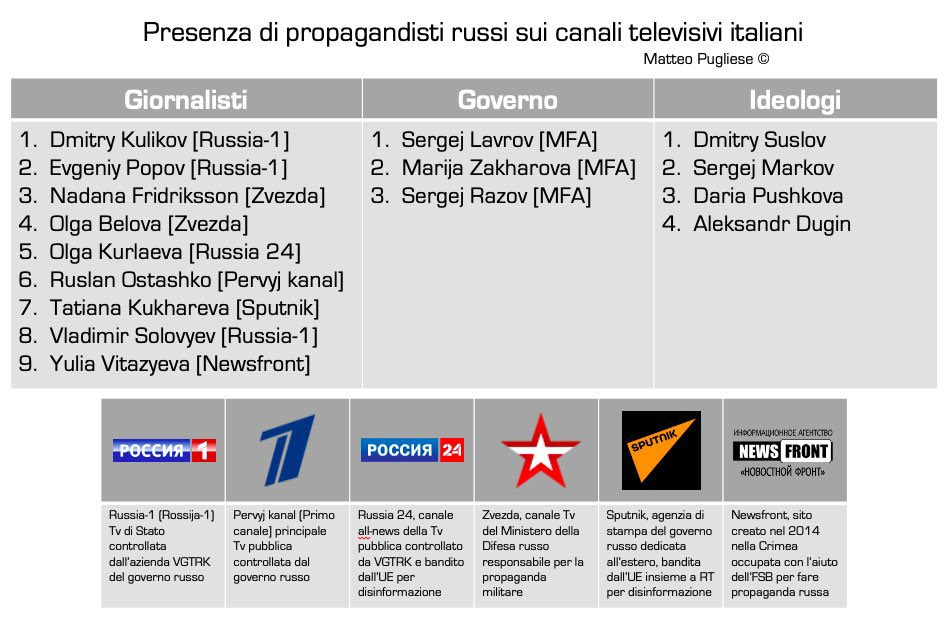

Russia’s disinformation operation started in March 2022 by activating an army of Italian Russlandversteher, pro-Kremlin intellectuals, and YouTubers, all of whom beat the drum of Russian propaganda: Russia was defending its population under threat; Ukraine was a failed state and an American puppet governed by Nazis; the West, and especially NATO, had provoked Russia. Italian political talk shows platformed representatives from the Russian Ministry of Defence, and Zvezda TV, without mentioning that they were agents of the Russian government. Sergey Razov, Russia’s ambassador to Italy, and Vladimir Solovyev, controversial host to Rossiya1’s prime time programme, were invited as guests and were legitimised by Italy’s flagship talk show several times to ‘give their side of the story’. An investigative programme, “Piazzapulita”, broadcast a three-part ‘documentary’ on the “Siege of Mariupol”, failing to disclose the fact that it was entirely filmed by the Russian army. [29]

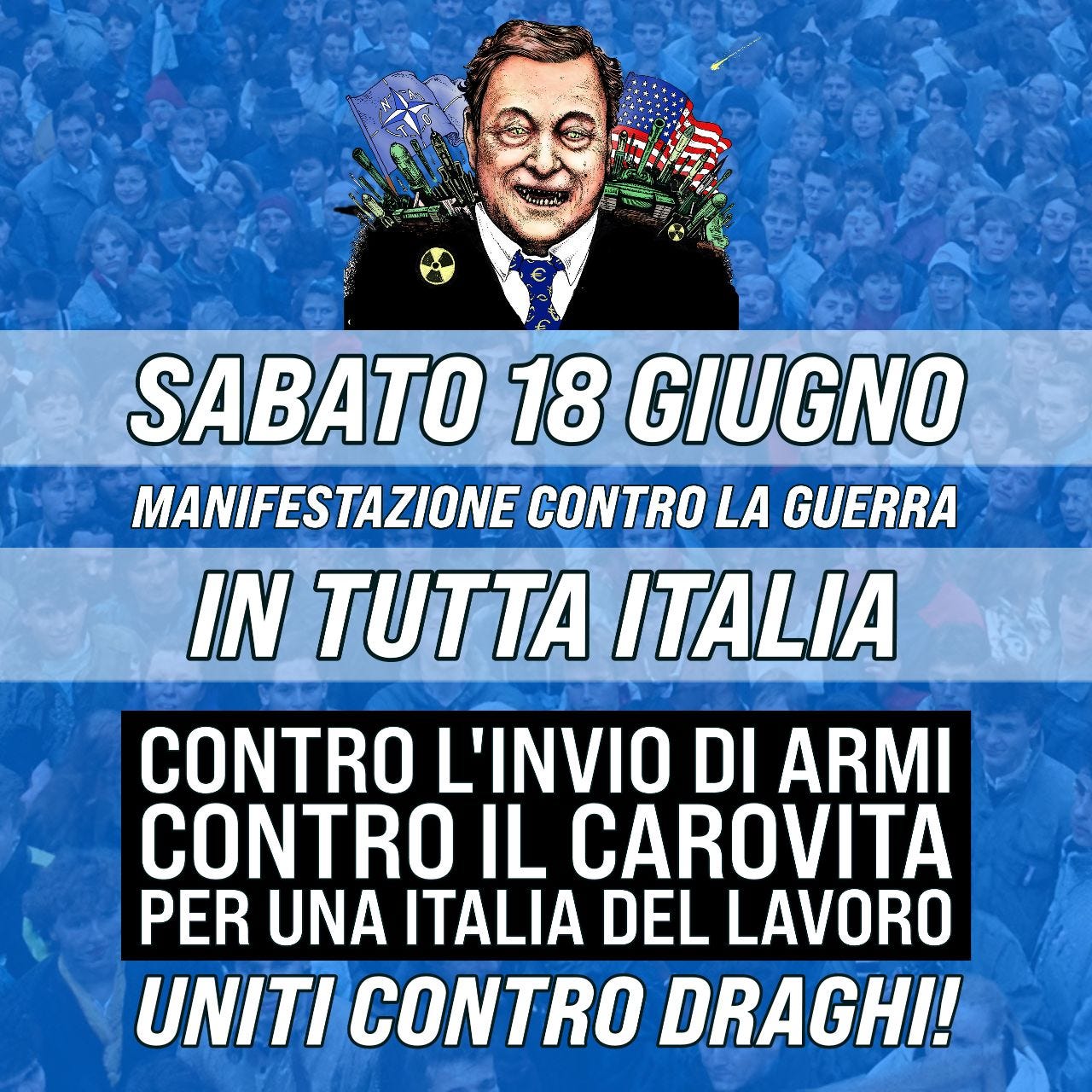

In June 2022, a series of micro-protests in many Italian piazzas were organised by a new party, Italia Sovrana, whose propaganda attracted anti-vaxxers, anti-American, and anti-NATO ‘protesters’. They demanded the unilateral disarmament of Ukraine, and ‘peace’ negotiations. The public servants’ union, CGIL, also organised a ‘peace’ rally during which a banner reading “I love Gazprom” was paraded through the streets of Rome. [30]

The M5S accompanied the wave of Russian propaganda in words and actions. Former Italian prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, and the M5S tried to weaken the government several times by opposing an increase in Italian defence spending to meet NATO commitments, and presented a resolution in parliament against NATO and Italian aid for Ukraine.

The Russians also activated Matteo Salvini. Investigations have revealed that in April 2022 Salvini’s foreign policy advisor, Angelo Capuano, was contacted by a United Russia party woman to organise a ‘peace mission’ for Salvini in Moscow. In mid-May, the Russian intermediary confirmed that Salvini was set to meet with Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, and the president of the Upper House of the State Duma, Valentina Matvienko. The contact directed Salvini’s advisor, Angelo Capuano, to contact Oleg Kostyukov, the embassy’s ‘political officer’, to finalise the arrangements for the trip. On the return leg, Salvini was supposed to stop in Beijing to meet with his Chinese counterpart. The Russian embassy would foot the bill entirely as per text messages on WhatsApp. According to a leaked intelligence dossier, Salvini had already met “confidentially with the Russian ambassador” in May, “with whom he also discussed a possible future trip of Pope Francis to Russia”. Once the details of the trip were disclosed by the Italian press, Salvini’s trip was cancelled. [31]

To the shock of most Italians, Mario Draghi’s premiership ended in mid-July 2022 when Giuseppe Conte’s M5S forced a non-confidence vote in parliament concerning continued support to Ukraine. Salvini and Berlusconi’s parties voted against Draghi’s proposals, bringing the Unity government, and Draghi’s premiership to a close.

The allegation that Draghi’s dismissal was orchestrated by Russia has not been confirmed officially. However, the events leading up to mid-July 2023 point to Russia’s intention to destabilise the Italian government, weaken support for Ukraine, and erode allied unity. It appears that Russia achieved its strategic aims through a massive information warfare campaign, and Salvini’s back-channel accords with Russian authorities, all of which may have been funded via the Russian embassy in Rome. Italian journalists, privy to intelligence reports, have revealed that in meetings with Capuano, Kostyukov asked him if Salvini and his ministers were “intentioned to resign from the Draghi government”. The intelligence officer concluded that the Russians were “interested in destabilising the balance of the Italian government”. In a public statement after the non-confidence vote, Enrico Letta, PD Party’s chief, said he “hoped that the people who pulled the plug on Draghi were not inspired by voices in Moscow or the Russian embassy. But there is no doubt […] that at the embassy, they’re celebrating with vodka and caviar”. [32]

Political and information warfare operations require funds. Recent media reports have unveiled that since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Russian embassy has withdrawn four million euro in cash from two current accounts in Rome. The Italian Financial Investigative Unit (GDF) was alerted as well as COPASIR by the Bank of Italy. Analysts at La Repubblica, the newspaper that broke the story, believe that the withdrawals were made to pay off “certain subjects” illegally without leaving a trace. [33] Sergio Germani, at the Germani Institute, agrees and says this strategy has been in practice since the Soviet era. He explained that, in the long-term, Russian intelligence aims to recruit "occult informants and agents of influence” who have access to “sensitive or classified documents of a political, military, economic or technological nature”. Germani added that the Russians have approached personnel working in political institutions, civil and military public administration, and strategic industries, who “can influence a political or economic decision-making process. The Russian services are also interested in using authoritative people as agents of influence who can convey the Kremlin's disinformation and propaganda messages to Italian public opinion". Italians are still waiting for clarity around the collapse of Draghi’s government. [34]

Conclusions

Since the Soviet era, Russia has sought to further its foreign policy aims in Western democracies through the use of active measures. Russia’s strategic aims focused on countering the power of the United States by weaking it and its allies. In order to do so, they employed forms of hybrid warfare. In Italy they’ve been highly successful for over a century. The Russians captured the Italian establishment, politicians, think tanks and journalists who have acted as agents of influence in support Russian foreign policy.

The Kremlin’s greatest achievement in furthering its foreign policy goals in Italy was through the growth and victory of the nationalist-populist parties—the League and the Five Star Movement. These parties brought Italy’s foreign policy perilously in line with Russian strategic aims, and opened the door to the Russian military and GRU agents, in breach of NATO and Italian national security. Furthermore, while investigations are still on-going, it appears that Russia orchestrated the demise of Mario Draghi’s premiership through disinformation operation to discredit Draghi and his government’s support of Ukraine. The League met secretly with Russian authorities, and former prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, actively pressed for ‘peace’ and ‘negotiations’, calling a non-confidence vote in parliament, which advanced Russia’s aims.

Russia’s victory, however, was partial: Georgia Meloni is now prime minister, and has continued Mario Draghi’s Euro-Atlanticist foreign policy. For the moment, she is still the leader of the Italian government.

Recommendations

In consideration of Russia’s continued political, psychological, cyber and energy warfare in Italy, the following recommendations are suggested for review: [35]

1) Weaknesses of the Italian economy and legal system must be addressed by Italian politicians in order to deprive Russian information warfare the leverage to manipulate and divide Italian society.

2) Italian legislators must amend the laws governing funding to political parties and lobbying firms. The loophole in the 2019 law allowing foundations, associations, and committees to receive undisclosed funding from foreign entities should be closed.

3) In view of Italy’s lack of transparency, legislators must establish a national registry of foreign donors to enhance transparency.

4) Stronger law-enforcement and counterintelligence measures are required to counter covert interference by foreign intelligence services in Italian politics, including covert funding.

5) A literacy programme should be introduced in the national school curriculum. Internet education should begin at an early age, and should follow the best practices of successful programmes instituted in the EU.

Special thanks

Without the seminal work done by Sergio Germani, and his team at the Germani Institute in Rome, and investigative reporters, Jacopo Iacoboni and Gianluca Paolucci, much of Russia’s non-kinetic warfare in Italy would still be hidden away.

This is the first of many papers I’ll be publishing about Russia’s past and continuing non-kinetic warfare in Italy. There’s so much more work to be done, especially regarding Soviet operations. The Russians planted many seeds in the 20th century, which took bloomed in the 21st.

[1] Intelligence and Security Committee of [UK] Parliament, “Russia”, House of Commons (21 Jul 2020). Online. https://isc.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/20200721_HC632_CCS001_CCS1019402408-001_ISC_Russia_Report_Web_Accessible.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2023.

[2] Germani, Sergio Luigi. “Covert and Overt Russian Operations and Influence in Italy: Report on Hybrid Threats,” Report presented to the Italian Senate during the conference on “FIMI Operations in Italy: A Comparison of the Russian and Chinese Approaches”. 19 July 2023. Online Conference. https://www.radioradicale.it/scheda/703976/le-strategie-di-influenza-e-ingerenza-di-potenze-straniere-in-italia-gli-approcci. Accessed 19 July 2023; Global Engagement Centre, “GEC Counter-Disinformation Dispatches #11: The Goals and Main Tactics of Russian Disinformation,” Online. https://e.america.gov/t/ViewEmail/i/CD46E76EEAD07F9E2540EF23F30FEDED. Accessed 13 Nov 2022; John Lenczowski, “Political-Ideological Warfare in Integrated Strategy,” in Douglas E Streusand, Norman A. Bailey, and Francis H. Marlo (eds.), The Grand Strategy that Won the Cold War, (Lanham, MD, Lexington Books, 2016). Online. Accessed 1 Nov 2023.

[3] Di Pasquale, Massimiliano, Sergio Germani, “L’influenza russa sulla cultura, sul mondo accademico e sui think tank italiani”, Istituto Gino Germani di Scienze Sociali e Studi Stranieri (Sept 2021), pp 4-6.

[4] Ibid, p 5.; For references on Italy’s long-standing relationship with the Soviet Union, see the following titles: Elena Aga-Rossi and Victor Zaslavsky. Togliatti e Stalin, Il PCI e la politica estera staliniana negli archivi di Mosca. Il Mulino, Bologna, 1997; Antonio Gramsci. Note su Macchiavelli, sulla politica e lo stato moderno, Editori Riuniti, Roma, 1996; Cantoni, Roberto. “Breach of Faith? Italian-Soviet Cold War Trading and ENI’s International Oil Scandal,” Quaestio Rossica. Online. https://hal.science/hal-01264554/document. Accessed 5 Nov 2023; Koshetz, Herbert. “Fiat’s Soviet Venture,” The New York Times. Online. https://www.nytimes.com/1972/01/23/archives/fiats-soviet-venture.html. Accessed 10 Nov 2023; Villani, Flavio. “How Italian Pop Music Conquered the Soviet Union.” New East Archive Org. Online. https://www.new-east-archive.org/features/show/12974/italian-pop-music-soviet-union-ciao-2020-roberto-loreti. 1 Nov 2023; Archive. “Fiat to Sign Agreement to Build New Line of Cars in the Soviet Union.” The Washington Post. Online. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/1989/11/28/fiat-to-sign-agreement-to-build-new-line-of-cars-in-soviet-union/0765aa85-60c7-420a-b183-8114ee8d4743/. Accessed 28 Oct 2023; Archive. “Italy and Soviet Union Sign Pact to $400 Million Annually by 1969.” New York Times. Online. https://www.nytimes.com/1964/02/06/archives/italy-and-soviet-sign-pact-to-expand-trade-to-400-million-annually.html. Accessed 28 Oct 2023.

[5] Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West. (Allen Lane The Penguin Press, 1999). chap 27.; Germani, Sergio Luigi. “Covert and Overt Russian Operations and Influence in Italy: Report on Hybrid Threats,” Report presented to the Italian Senate during the conference on “FIMI Operations in Italy: A Comparison of the Russian and Chinese Approaches”. 19 July 2023, p. 4. Online Conference. https://www.radioradicale.it/scheda/703976/le-strategie-di-influenza-e-ingerenza-di-potenze-straniere-in-italia-gli-approcci. Accessed 19 July 2023; Director of Central Intelligence, “Soviet Support for International Terrorism and Revolutionary Violence: Special National Intelligence Estimate”, 27 May, 1981. Online. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP90T00155R000200010009-2.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

[6] Ibid, pp 4-5.; The false manual released: US Army Field Manual 30-31B, “Stability Operations Intelligence- Special Fields”, (1970). Wayback Machine Online. https://web.archive.org/web/20170423090655/http://jim-garrison.livejournal.com/37233.html. Accessed 17 Nov 2023; Cavallo, Lorenzo. “Le stragi in Italia e il presunto manuale 30-31B della US Army”, Avanti Online. https://www.avantionline.it/le-stragi-in-italia-e-il-presunto-manual-30-31b-della-u-s-army/. Accessed 17 Nov 2023; NGO Watchlist, “Russkiy Mir”, Institute of European Integrity. Online. https://www.iei.ngo/ngo-watchlist/russkiy-mir-foundation. Accessed 18 Nov 2023.

[7] Belton, Catherine, Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took On the West (Harper Collins, 2020), pp. 33-36; Germani, Sergio Luigi. “Covert and Overt Russian Operations and Influence in Italy: Report on Hybrid Threats”, p. 4; Iacoboni, Jacopo, Oligarchi (Editori Laterza, 2021) pp 86-88.; Jacopo Iacoboni, “Berlusconi-Putin connection: gas supplies, maxi contracts for the Kremlin TV and former KGB agents, La Stampa. Online. https://www.lastampa.it/politica/2022/10/21/news/berlusconiputinconnection_forniture_di_gas_maxi_appalti_per_la_tv_del_cremlino_ed_ex_agenti_del_kgb-12183537/. Accessed 10 Nov 2023; For information regarding Antonio Fallico and his is work with the association “Conoscere Eurasia”, ; see: NGO Watchlist, “Russkiy Mir”, Institute of European Integrity. Online. https://www.iei.ngo/ngo-watchlist/russkiy-mir-foundation. Accessed 18 Nov 2023; Conoscere Eurasia Website, “Conoscere Eurasia Brochure”, Online. https://conoscereeurasia.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Brochure_it.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2023.; Antonio Fallico is also an Honorary Russian Consul, see: Honorary Russian Consulate in Verona https://consolatorussoonorario-vr.it/. Accessed 10 Nov 2023; Ligorio, Benedetto. “Verona verso una nuova economia umanistica”, Avanti. Online. https://www.avantionline.it/verona-forum-economico-euroasitatico-evolvere-verso-una-nuova-economia-umanistica/. Accessed 22 Nov 2023.

[8] Germani, Sergio L., “Russian Active Measures and the Populist Surge in Italy (2013-2019),” Confidential Draft. Presented at the Conference “Russian Active Measures: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow” European University Institute, 23-24 May 2019.

[9] Ibid, p 5.

[10] Ibid, p 6.; Biondani, Paolo, “Soldi da Mosca alla Lega: al Metropol con Savoini c’era una spia di Vladimir Putin”, L’Espresso. Online. https://lespresso.it/c/inchieste/2021/6/24/soldi-da-mosca-alla-lega-al-metropol-con-savoini-cera-una-spia-di-vladimir-putin/22332. Accessed 15 Nov 2023.

[11] Germani, Sergio and Jacopo Iacoboni, in the Atlantic Council report The Kremlin’s Trojan Horses 2.0 (Nov 2017) p 11-19.; Savino, Giovanni. “From Evola to Dugin: The Neo-Eurasian Connection to Italy”, in Marlene Laruelle (Editor) Eurasianism and the European Far Right: the Future Europe-Russia Relationship (Lexinton Books, 2015).

[12] Germani, Sergio L., “Russian Active Measures and the Populist Surge in Italy (2013-2019),” Confidential Draft. Presented at the Conference “Russian Active Measures: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow” European University Institute, 23-24 May 2019, p 6.; Catto, Alessandro. “Associazione Lombardia-Russia: uno sguardo geopolitico per una nuova amicizia con Mosca”, Blog, Il Giornale. Online.

https://blog.ilgiornale.it/catto/2015/12/02/associazione-lombardia-russia-uno-sguardo-geopolitico-per-una-nuova-amicizia-con-mosca/. Accessed 12 Nov 2023; NGO Watch List, “St Basil The Great Foundation”, Institute for European Integrity. Online. https://www.iei.ngo/ngo-watchlist/st-basil-the-great-foundation. Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

[13] Germani, Sergio L., “Russian Active Measures and the Populist Surge in Italy (2013-2019),” p 7; Announcement for the opening of the DPR consulate in Verona on “Associazione Veneto-Russa” Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/venetorussia/photos/inaugurazione-dellufficio-di-rappresentanza-della-repubblica-popolare-di-donetsk/770423316666577/. Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

[14] Germani, Sergio L., “Russian Active Measures and the Populist Surge in Italy (2013-2019),” pp 8-14.

[15] Ibid, p 16.; Picardi, Andrea. “Tutti le fregole filo-Putin del Movimento 5 Stelle”, Le Formiche. Online. https://formiche.net/2017/03/m5s-putin-russia-grillo/. Accessed 10 Nov 2023; Smagliy, Kateryna. “Hybrid Analytica: Pro-Kremlin Propaganda in Moscow, Europe and the U.S.”, Institute of Modern Russia (Oct 2018). Online. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59f8f41ef14aa13b95239af0/t/5c6d8b38b208fc7087fd2b2a/1550682943143/Smagliy_Hybrid-Analytica_10-2018_upd.pdf. Accessed 31 Oct 2023.

[16] Germani, Sergio L., “Russian Active Measures and the Populist Surge (2013-2019)”, p 11.; Staff, “M5S, Di Maio: ‘Seria emergenza migranti, Minniti e chi dice il contrario è fuori dal mondo”, La Repubblica. Online. https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2017/06/14/news/migranti_di_maio_emergenza_c_e_-168067716/. Accessed 24 Nov 2023; BBC, “Migration crisis: Russia and Syria ‘weaponise’ migration, BBC News (2 Mar 2016). Online. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35706238. Accessed 24 Nov 2023.

[17] Results for the 2018 General Elections, Il Sole 24 Ore. Online. https://st.ilsole24ore.com/speciali/2018/elezioni/risultati/politiche/static/italia.shtml. Accessed 20 Nov 2023.

[18] Reuters. Online. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-italy-russia-putin-conte/putin-visiting-italy-says-wants-rome-to-help-mend-moscow-eu-ties-idUSKCN1TZ1WL/. Accessed 19 Nov 2023; TASS, “Putin to visit Italy 4 July, to meet with Pope in Vatican”, Online. https://tass.com/politics/1066557. Accessed 21 Nov 2023; Rosato, Antonangelo. “A Marriage of Convenience? The Future of Italy-Russia Relations”, European Council on Foreign Relations. Online. https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_a_marriage_of_convenience_the_future_of_italyrussia_relations/. Accessed 12 Nov 2023.

[19] Iacoboni, Jacopo, Oligarchi, p 137.; Also see: Iacoboni, Jacopo. “I misteri degli aiuti russi in Italia”, La Stampa. Online. https://www.lastampa.it/esteri/2022/03/20/news/il_mistero_degli_aiuti_russi_nell_italia_in_pieno_lockdown-2877428/. Accessed 22 Nov 2023.

[20] Iacoboni, Jacopo, Oligarchi, p 133.

[21] Iacoboni, Jacopo. “I misteri degli aiuti russi in Italia”, La Stampa. Online. https://www.lastampa.it/esteri/2022/03/20/news/il_mistero_degli_aiuti_russi_nell_italia_in_pieno_lockdown-2877428/. Accessed 22 Nov 2023.

[22] Bastasin, Carlo. “Italy loses Draghi for Leader—for now”, Brookings Institute. Online. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/italy-loses-draghi-as-its-leader-for-now/. Accessed 22 Nov 2023; Cifoni, Luca. “Draghi, la sfida di SuperMario: dopo l’Europa, l’Italia. Con “Whatever it takes” salvò l’euro” Il Corriere. Online. https://www.ilmessaggero.it/politica/mario_draghi_governo_chi_e_presidente_consiglio_mattarella-5741137.html. Accessed 5 Nov 2023.

[23] Iacoboni, Jacopo, Oligarchi, pp XI-XVI.

[24] Caruso Carmelo. “Mario Sent Me”, Il Foglio. Online. https://www.ilfoglio.it/politica/2022/03/23/news/draghi-ribadisce-sostegno-all-ucraina-ma-in-parlamento-e-sempre-il-donbas-3833904/. Accessed 20 Nov 2023; De Luca, Alessia. “Draghi, Macron, Scholz, and Iohannis in Kyiv”, Italian Institute for Political Studies. Online. https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/draghi-macron-scholz-e-iohannis-kiev-35461. 19 Nov 2023.

[25] Roberts, Hanna. “Mario Draghi’s enemies are doing Putin’s work, minister says”, Politico. Online. https://www.politico.eu/article/italy-luigi-di-maio-ukraine-war-politics-weapon/. Accessed 7 Nov 2023; SkyNews24, “Elezioni Sondaggio: Quorum/YouTrend per SkyTG24: Intenzioni di voto premiano FdL e PD”, SkyNews. Online. https://tg24.sky.it/politica/2022/07/25/elezioni-sondaggio-quorum-youtrend#00. Accessed 21 Nov 2023; Decode39, “Draghi’s Paradox: liked abroad, crisis at home”, Decode39. (30 Jun 2022) Online. https://decode39.com/3708/draghi-paradox-crisis-home/. Accessed 21 Nov 2023.

[26] Comitato Parlamentare per La Sicurezza della Repubblica (COPASIR), Relazione sull’attività svolta dal 10 febbraio 2022 al 19 agosto 2022, presented by Sen. Adolfo Urso, The Italian Senate. Online. https://www.senato.it/service/PDF/PDFServer/BGT/1360852.pdf. 21 Nov 2023, pp 34-57.

[27] Albarese, Chiara. “Italy Boosts Cybersecurity with a New Unit Under Draghi”, Bloomberg. Online.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-10/italy-moves-to-boost-cybersecurity-with-new-unit-under-draghi?embedded-checkout=true. Accessed 20 Nov 2023; Speciale, Alessandro, Chiara Albanese, John Ainger. “Draghi Bets on Africa for Italy’s Exit from Russian Gas”, Bloomberg. Online. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-14/draghi-bets-on-africa-to-speed-up-italy-s-exit-from-russian-gas?embedded-checkout=true. Accessed 10 Nov 2023;

[28] Roberts, Hanna. “Mario Draghi’s enemies are doing Putin’s work, minister says”, Politico. Online. https://www.politico.eu/article/italy-luigi-di-maio-ukraine-war-politics-weapon/. Accessed 7 Nov 2023.

[29] Iacoboni, Jacopo, I Tesori di Putin (Laterza Editori, 2022), pp 7-9; Roonemaa, Holger. Martin Laine. Michael Weiss, “Exclusive: Russia Backs Europe’s Far Right”, New Line Mag, Online. https://newlinesmag.com/reportage/exclusive-russia-backs-europes-far-right/. Accessed 21 Nov 2023; Piazzapulita, “The Siege of Mariupol”, (09/06/2022), YouTube. Online.

. Accessed. 10 June 2022.; Tondo, Lorenzo. “’A Success for Kremlin Propaganda’: How pro-Putin views permeate Italian media”, The Guardian (31 Aug 2023). Online. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/31/a-success-for-kremlin-propaganda-how-pro-putin-views-permeate-italian-media. Accessed 19 Nov 2023.

[30] Please note: pictures of the CGIL rally held in Rome were publicly available on social media. After seeing the banner “I love Gazprom”, I wrote an email to the national and local administrators of the union. I was told that it was an isolated incident. However, Gazprom banners have featured in other rallies. Staff, “I ponti e le bollette”, La Repubblica. Online. https://invececoncita.blogautore.repubblica.it/articoli/2022/10/11/i-ponti-e-le-bollette/. Accessed 24 Nov 2023.

[31] Iacoboni, Jacopo. “Russian shadows behind the crisis” (28 July 2023). Online. https://www.lastampa.it/politica/2022/07/28/news/ombre_russe_dietro_la_crisi_cosi_gli_uomini_di_putinsinteressarono_alla_possibile_caduta_del_governo_draghi-5480837/. Accessed 15 Nov 2023.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Carrer, Gabriele, “Suspect Russia cash movement trigger Italian Intelligence alert”, Decode39. Online. https://decode39.com/8256/suspect-russia-cash-movements-trigger-italian-intelligence-alert/. Accessed 15 Nov 2023; Scarpa, Giuseppe and Giuliano Foschini, “The Russian embassy in Rome in the sights of intelligence: 4 million in cash withdrawn, alarm from the Bank of Italy”, La Repubblica (14 Nov 2023). Online. https://roma.repubblica.it/cronaca/2023/11/14/news/ambasciata_russa_roma_intelligence_prelevati_4_milioni_allarme_banca_ditalia-420350036/. Accessed 15 Nov 2023.

[34] Germani’s statements in Carrer, Gabriele, “Top Secret Information and Propaganda”, Le Formiche. Online. https://formiche.net/2023/11/informazioni-e-propaganda-spie-putin-in-italia/. Accessed 15 Nov 2023; Lautman, Olga, “Western Elites- Rubles Bought (Some of) the Best”, the Centre for European Policy (30 Jan 2023). Online. https://cepa.org/article/western-elites-rubles-bought-some-of-the-best/. Accessed 20 Nov 2023.

[35] Banks, Daniel. “The Corruption of Italian Democracy: Russian Influence over Italy’s League.” Online. https://globalanticorruptionblog.com/2022/04/08/russian-influence-over-italys-league/. Accessed 31 Oct 2023; Germani, Sergio L., “Russian Active Measures and the Populist Surge in Italy (2013-2019),” pp 20-20.

I would also suggest the russians are using Havana syndrome type technology. The tech is similar to what china calls ints neurostrike system. The indian press has reported on neurostrike, and the american neuroscientist Dr James Giordano explains clearly and frightening how advanced these weapons have become. Great reporting! Thank You =]