Who is Yevhenii Monastyrskyi…

Yevhenii Monastyrskyi is a Luhansk (eastern Ukraine) native historian of the Soviet Union and a sociologist. Before the outbreak of the war, he was studying history at the Luhansk Taras Shevchenko National University. After fleeing his hometown in October 2014, he has studied at the Ukrainian Catholic University (Lviv) and was visiting assistant in research at Yale University. In 2018 he was a Global Dialogues Fellow at The New School for Social Research (New York).

Before Yale, he was a research lead at War Childhood Museum Ukraine, simultaneously heading education reform support at the EU-funded program “House of Europe”, and serving as head of research for Charitable Foundation “Stabilisation Support Services”.

Yevhenii Monastyrskyi: The History of Donbas

The territory of modern Donbas was part of a vast ethno-contact zone known as part of the medieval Wild Steppe (or Wild Fields – Dyke Pole). That is, it was territory over which none of the macroregion's state formations had effective control.

The Ukrainian steppe was a medieval frontier, a place between trade caravans routes from Asia to Europe and back, as well as a site of periodic clashes and attempts at a coexistence between different peoples.

With the Mongol Empire's feudal fragmentation, the situation began to become more or less stable. Tatars and Nogai roamed the steppes at the time. Slavic farmers who settled along rivers in what is now Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts were frequently ravaged by nomads.

Although Tatars did not welcome the settlement of Wild Steppe, by the 15-16 c., an increasing number of peasants fleeing serfdom in the Rzeczpospolita and the Tsardom of Muscovy were making their way there. The outline of the Wild steppe as a "melting pot" started to emerge.

Around the same time (late 15th-16th c.), groups of Cossacks appeared on the steppes of eastern Ukraine, made up of Ukrainians fleeing colonial powers. It was not a natural search for new territories; rather, it was an attempt to make feudal lords leave them alone.

By the end of the 16th – beginning of the 17th centuries, Cossacks had established noticeable settlements along the Donets River, including Bakhmut, Osynovyi Ostroh, and Novopskov. Simultaneously, salt production begins in Bakhmut and Tor (now Sloviansk).

Cossacks, being a military force controlling the borders with the Crimean Khanate, outlined their political weight in the early 17th century during the "Time of Troubles" in Muscovy - everyone wanted their support in the fight to seize the throne after the death of Ivan IV.

Sviatohirsk Cave Monastery, founded in 1547, is particularly noteworthy. According to some sources, a Christian settlement existed in these areas as early as the 12th century. The monastery was and still is the largest Christian center in the region.

The steppe east of Ukraine became a deep rear for the Ukrainians during the Cossack uprisings from the late 16th to the mid 17th centuries. Following unsuccessful clashes with the Poles, Cossack detachments withdrew to the "Wild Steppe."

Following the Pereiaslav Agreement (1654), left-bank Ukraine became subservient to Muscovy, and the Ukrainian steppe grew as its southern outpost. In the 17th-18th c. the region was gradually populated by "Cherkassy" and “Khartzyzy” (Ukrainians from the central Dnipro region).

By the early 18th century, the eastern Ukrainian steppes had been a place of freedom from serfdom and a military frontier with the Crimean Khanate. And Bakhmut becomes the region's focal point, serving as the region's salt capital and main fortification.

Following the destruction of Zaporozhian Sich in 1709, Cossacks were once again permitted to settle in the Wild Steppes only in 1734. Then they established the Kalmiusskaya Palanka (military region) with its headquarters in Domakha (now the territory of Mariupol).

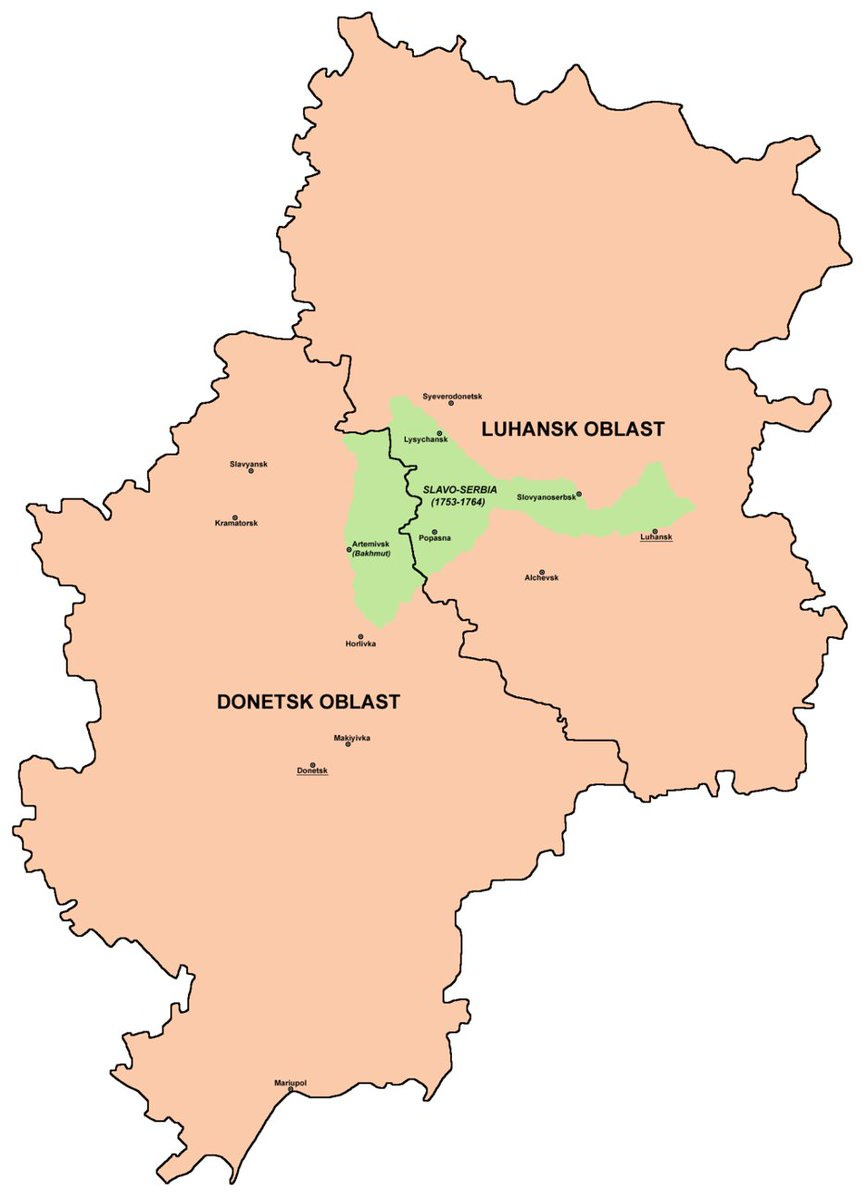

Following the Russian-Turkish war of 1735–39, the RU Empire gained control of the Azov sea region, necessitating the settlement of the steppes in preparation for another war. As a result, Serbs and Croats from the Ottoman Empire were invited to settle in Ukraine's steppes.

Serbs and Croats were given land between the Bakhmut and Luhan rivers, it was called Slavo-Serbia. Though, settlers from Balkans were not coming in sufficient numbers, so Ukrainians and Moldovans from southern Ukraine were sent there.

The Greeks who "came out of the Crimea" settled in the east of Ukraine at the end of the 18th century. They settled along the Kalmius River and including Mariupol and surrounding areas – that's where names like Nova Yalta (New Yalta) or Stary Krym (Old Crimea) came from.

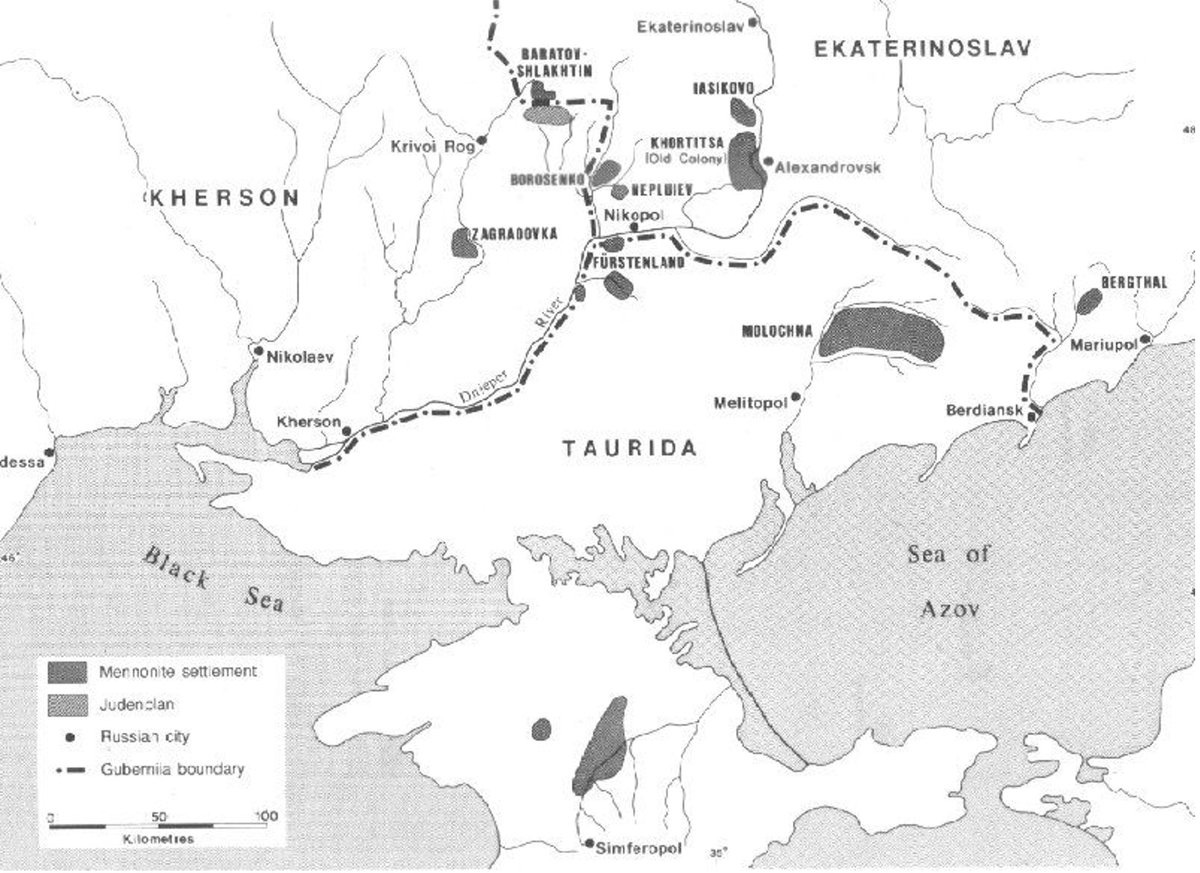

German Mennonites settled in eastern Ukraine in the first half of the 19th century, with a sizable number settling near Mariupol. They were farmers, but after the introduction of compulsory military service for colonists in the 1870s, they fled Ukraine for North America.

After the Partitions of 🇵🇱 at the end of the 18th c, the 🇷🇺 Empire had the greatest number of Jews in Europe. They began to migrate within the Pale of Settlement, which included east of Ukraine. By the mid-19th c, the Bakhmut population was 15% Jewish, including my family.

Steppe Ukraine began to transform from an early-modern frontier where people sought freedom for themselves into an industrial center. Initially, the industry was based on salt mining, with "chumaks" (traders and carriers of goods) serving as the backbone of the local economy.

Coal mining started in eastern Ukraine in the 1720s (again in Bakhmut, see map), but it was not effective mostly due to serfdom and lack of technology. Coal mining was seasonal in the 18th century in Ukraine’s east, peasants were working in coal mines sporadically at best.

After the 🇷🇺 Empire's defeat in the Crimean War, reforms (particularly the abolition of serfdom) and industrialization began. Previously, coal mining was carried out not only by landowners but also by Cossacks and peasants. However, there was no technology and no railroads.

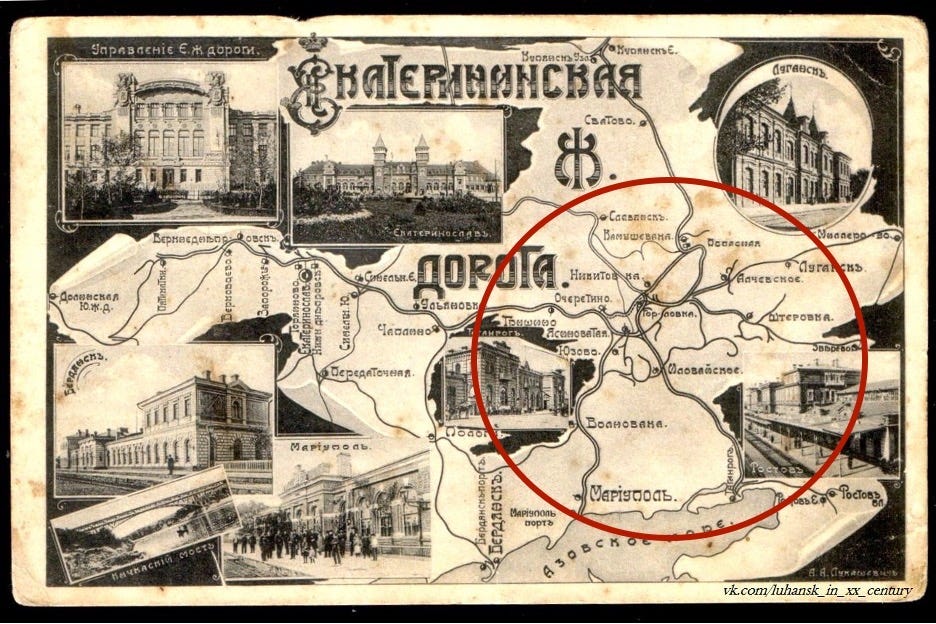

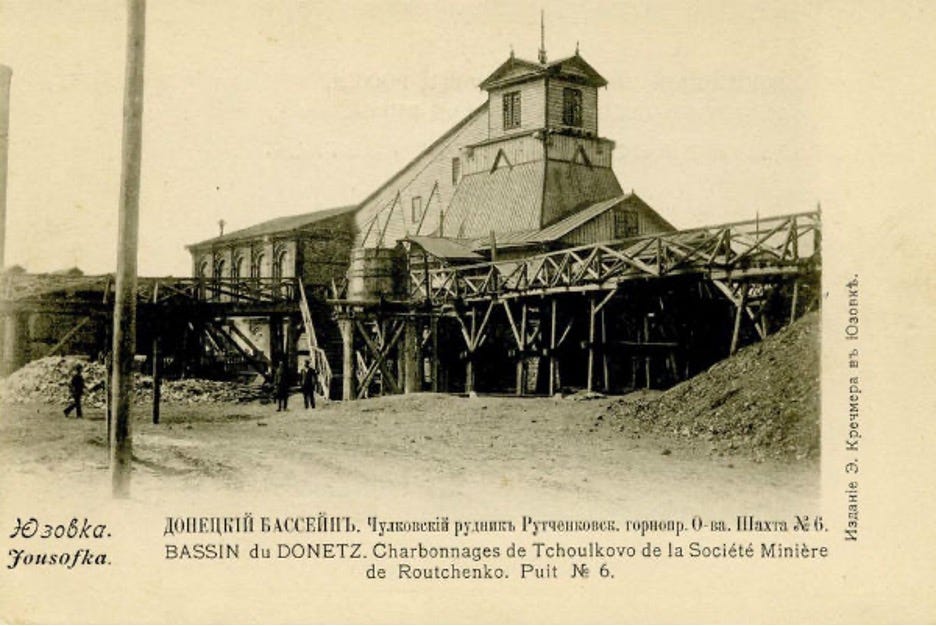

Eastern Ukraine's steppes finally received an integrated railroad system by the 1870s. This created favorable conditions for foreign capital looking for a location for its operations. This is how the Donbas – Donetsk Coal Basin – was created.

The incentives for foreign investment transformed the Donbas into one of the Russian Empire's fastest-growing industrial centers. In the 1870-90s, French, German, British, Belgian, and other European entrepreneurs established businesses there.

Imperial modernization attracted a large number of immigrants; by the early 20th century, 26% of Donbas residents were from other provinces. People moved to large cities from Russian provinces in search of employment in metallurgical industries.

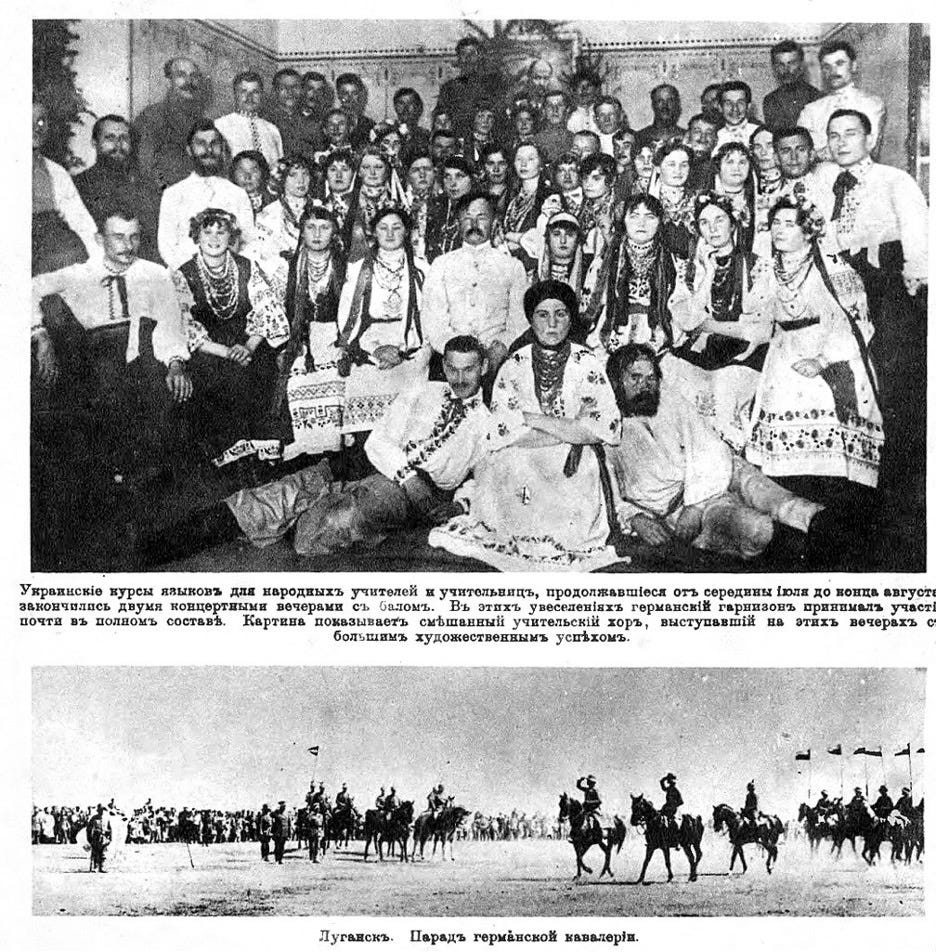

At the same time, the Donbas rural majority remained ethnically monolithic: Ukrainians (some of whom moved to the region during the 19th century from central Ukraine) and some settlements-colonies of Germans, Jews, and Greeks working in agriculture.

However, do not mistake quantitative dominance of Ukrainians in the region for cultural dominance. The region's russification came at the expense of establishing russian as the "language of the city," and the gentrification of Ukrainian settlements meant their russification.

The 🇺🇦-speaking population in the Donbas was eroded by the ghettoization of the 🇺🇦 language, despite the short period of Ukrainization in 1920-30s. My ancestors, for instance, who have lived in the Donbas since the 17th century, spoke Ukrainian at home until the 1950s.

And, while the Holodomor had a lesser impact on the Donbas cities, the small towns and villages where the majority of Ukrainians lived were devastated. At the time, my grandmother lived in the small mining town of Rovenki, and her grandfathers have perished in the famine.

After WWII, the devastated Donbas went through a difficult reconstruction. Many evacuated never returned, many died, >95% of Jews died in the Holocaust. The region was repopulated, frequently by russians. The city spoke Russian, and the villages were forgetting Ukrainian.

The steppe east of 🇺🇦 was an early modern frontier that Ukrainians have long settled. Resemblance to the "wild west" can only be attributed to the fact that, in the end, an empire arrived and sought to exterminate the native population.

It is a story about #russianColonialism.