Jan 31: Sonia Savina, Why is the Ukrainian population declining under Putin

As published in iStories on January 24, 2023

Sonia Savina, Why is the Ukrainian population declining under Putin? iStories

The cleansing of everything Ukrainian in Russia began long before the full-scale war

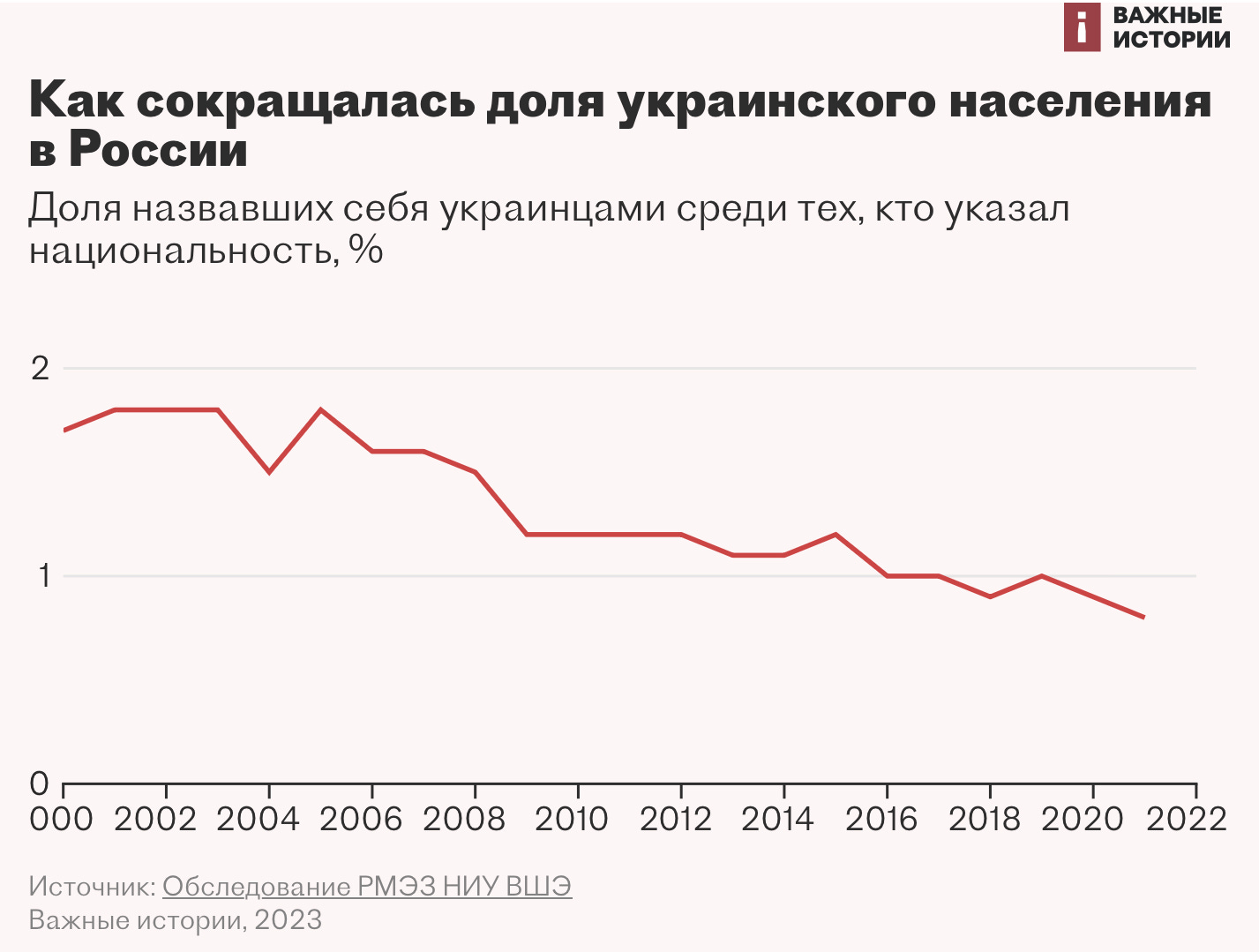

The 2021 All-Russian Population Census showed a record reduction in the number of Ukrainians in Russia: it has halved in ten years. And although experts question the results of the census, the same trend is recorded by data from other studies, demographers, and representatives of the Ukrainian diaspora themselves. "Important Stories" tells how the Russian authorities eradicated Ukrainian identity from their own citizens long before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine - from the very beginning of Vladimir Putin's presidency.

Record decline

Ukrainians have historically been one of the most highly represented nationalities in Russia: just a decade ago, they were the third largest group (about two million people), after ethnic Russians and Tatars, according to census data. By 2021, however, they’d fallen to the eighth spot (about 884,000 people).

While Russia’s Ukrainian population has been gradually shrinking for decades, this sudden decline of more than half was unprecedented. Other data sources show the same pattern: according to the Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey conducted by Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, while Ukrainians made up almost 2 percent of Russia’s population in the 2000s, they made up less than 1 percent in 2021.

What could this mean

Demographer Alexey Raksha believes the most likely reason for the apparent decline in Russia’s Ukrainian population is that Ukrainians, especially young ones, tend to start self-identifying as Russians sooner after moving to Russia than people of other ethnicities do. It may also be the case that Ukrainians are leaving Russia faster than they’re immigrating there, Raksha said, though reliable data here are scarce.

According to members of Russia’s Ukrainian diaspora, the shift hasn’t been a natural process, regardless of whether the decrease is due to emigration or a change in how people self-identify. They say the Russian authorities have been working to reduce the country’s Ukrainian population for years, namely by discouraging expressions of Ukrainian identity and shutting down organizations that represent Ukrainians’ interests in Russia.

“Now it’s not safe to admit that you are Ukrainian”

“Being an ethnic Ukrainian in Russia has become uncomfortable,” Viktor Girzhov, former deputy chairman of the Association of Ukrainians in Russia, explains the results of the census. He lived in Russia for over 20 years, but in 2015 the FSB banned him from entering the country for five years. Formally, for violating the procedure for entering and leaving the country, but Girzhov himself believes that he was expelled for telling the truth about what is happening in Ukraine on Russian central television channels.

Viktor Girzhov considers the official state policy aimed at clearing the entire Ukrainian field in Russia one of the main reasons why there are fewer Ukrainians. According to him, this began after 2004, when the “orange revolution” took place in Ukraine, and some Ukrainian organizations in Russia supported it. “After the collapse of the Union, Ukrainian organizations began to appear in Russia like mushrooms after the rain. There was such euphoria, such a mood that under Gorbachev, under Yeltsin there would be some kind of freedom ... - says Girzhov. “And then something clicked, and it all started to fall apart — it happened under Putin.”

Girzhov tells how in 2010 and 2012 two federal organizations of the Ukrainian diaspora were liquidated: “Association of Ukrainians in Russia” and “Federal National Cultural Autonomy of Ukrainians in Russia”, which were engaged in the preservation of Ukrainian identity and the development and dissemination of Ukrainian culture. In 2018, the only world-famous library of Ukrainian literature in Moscow was liquidated. “Allegedly, there were some violations of the documentation in the statutory activities of [organizations]. But this is all sucked from the finger: if there were any small flaws, all this is corrected in a second. The director of the library was tried for allegedly possessing nationalist literature, although [the library] employees said that the security forces themselves planted these materials,” says Girzhov.

By the mid-2000s, Russia no longer had the opportunity to study the Ukrainian language, says Girzhov: “In Ukraine [then] there were a lot of schools teaching Russian. And in Russia, for the entire two-million diaspora, there was not a single school, not even a class with Ukrainian. In Russia, there is no way to communicate in Ukrainian: there are no schools, no libraries [with Ukrainian literature].” Together with other representatives of the Ukrainian diaspora, he tried to open the only Ukrainian school in Moscow, but the relevant departments “all the time put forward unrealistic demands, and everything died out.” Now, according to the 2021 All-Russian Population Census, only 33% of Ukrainians living in Russia speak Ukrainian.

There are almost no associations of Ukrainians left in Russia, says Girzhov. “Formally, such organizations exist, but they live on the money of the [Russian] government and presidential grants, and the authorities arrange what I call “sharovarschina”: these organizations participate in city holidays and festivals, dance and sing, but no politics, no social activity, no rights for Ukrainians,” says Girzhov. “These are such sharovary Ukrainians that suit the Russian authorities. And as soon as you start supporting Ukraine, not even the Maidan, but just independence, culture, language - that’s all.”

“Religious freedom of conscience, language proficiency, culture - this is what lives in people. Ethnos is what distinguishes one from the other, that it has some of its own cultural and national characteristics. There is an Armenian diaspora, there is a Georgian one. They are pleased to get together, sing songs, speak their own language. This is what a multinational Russia is – all peoples must mutually exist and mutually enrich themselves. Girzhov continues. - And this cultural environment was constantly cleaned up and banned in Russia: people are drawn to their national roots, and they are constantly chopped off. This gives rise to conflicts between nations.”

According to Girzhov, the decrease in the number of Ukrainians in the census can also be explained by the fact that not all ethnic Ukrainians in Russia identify themselves as such when answering the question about nationality. “People are afraid because now it is not safe to admit that you are Ukrainian,” says Girzhov. - For example, the FSB called people from the register of readers of the Library of Ukrainian Literature for interviews. Older people have children and grandchildren, they are worried. Younger people are afraid of losing their jobs. Whoever could, left before the war,” says Girzhov. “Now it’s difficult, so until the end of the war, the rest try not to emphasize their “Ukrainianness” – this is fraught.”

“Ukrainians were invited: ‘You sing in Russian’”

Valery Semenenko moved to Moscow from Ukraine in 1978 to enroll in graduate school and stayed. He is one of the founders of the "Association of Ukrainians in Russia" and from 2005 to 2012 was a co-chairman of the organization until it was closed by the Russian authorities. “At first, in the late 2000s and in the 2010s, we wrote letters, appeals addressed to Putin: we called for mutual understanding [between Russia and Ukraine], for taking into account interests. This is wrong: we live here, we should be friends. We were closed for this: after the “orange revolution” in Russia, the authorities started up. And two months after the closure, they created a puppet federal organization of Ukrainians, whose representatives now say on television that we are all Russians,” says Semenenko. “Now they periodically hold demonstrative [government] meetings on interethnic politics. Ukrainians used to sit at the head of the table: of course, we are your greatest friends! And now they are invited, then they call back: “Don’t come to the meeting.”

Now Semenenko heads a public association of Ukrainians in Russia, which operates without legal registration. “Now the Ukrainians of Russia are sitting underground. In fact, there is no public activity — it’s dangerous… We know Russian law: we can only write about the pain and suffering of Ukrainians, but of course, we can’t write about military operations, let alone discuss the [Russian] army. And we can help: people are fleeing from shells, from bombs, we help them get from the border. But even this help is not welcomed in Russia,” says Semenenko. You can't even sing. In the fall of 2022, there was an annual concert in St. Petersburg: there, each association - Kalmyks, Chuvashs - is given one number, they perform. Ukrainians were also invited. Then they realized: “Come on, sing in Russian.” They concluded: “Either we sing in Ukrainian, or we don’t sing.”

“This is a general trend towards the denial of Ukrainian identity,” he continues. “Now they [authorities and propagandists] are already openly saying that there are no Ukrainians and there weren’t, and there was no Ukrainian language, and all these are notions.” Semenenko does not believe the results of the census, but also notices that the number of Ukrainians in Russia is declining: “I know how these censuses are conducted. Everyone shouted: “Census, census, census!” But no one came to us. And I personally went to the council, I said: “How did they register us? Nobody asked me. I want us all to be registered as Ukrainians: me and my children.” They never showed me those papers. But the trend is indeed such that the number of ethnic Ukrainians is sharply declining.”

“If Russia [after the war] remains in the form of an undisintegrated state, and all these trends continue, there will be zero Ukrainians here,” Semenenko said. He admits that he always feels the desire to leave Russia: “But I am connected here: my house, my family, and my wife are a native Muscovite, well, where will she go? We should have left earlier. Now I’ll let my children go."

“Mom, I won’t go to fascist Russia”

Anna (name changed at the request of the heroine) from Chernigov has been living in Russia for more than 20 years and heads one of the associations of Ukrainian women in Russia. Every time an air raid alert sounds in Chernigov, she “hears” it at her home in the Moscow region: Anna follows the notifications, because her adult daughter remains in Chernigov. When the war began, Anna invited her daughter to evacuate to Russia: “I told her:“ Come here. And she replied: “No, mother, I will not go to fascist Russia.”

As Anna says, she does not trust the results of the census, but she also feels that there are fewer Ukrainians in Russia: “The census was carried out like this: we have an entire street of resident Ukrainians - no one even showed his nose and did not ask who we are, what we are. But now there are much fewer Ukrainians coming here. I have been here since 2000: so many Ukrainians came for work... My friend opened a construction company, there were 300 Ukrainians in the team. And now nobody, the company has closed.

“When I first arrived, in the early 2000s, everything was developing so rapidly: we [representatives of the Ukrainian diaspora] met with the authorities, talked about opening a Ukrainian school…” continues Anna. - And it seemed to us that Russia is so big, so much work, so much could be done, communicate with countries, exchange students, artist exchanges. We thought it would be like this, but it's completely different. The Ukrainian diaspora is now in a very deplorable state. If you say what the local authorities say, then, of course, the authorities will support you. But I don’t know how you can say something that doesn’t exist.”

Anna says that some acquaintances from Ukraine have stopped communicating with her only because she now lives in Russia. “But what can I do here alone? Anna asks. - Recently, people who care, took flowers to the monument to Lesya Ukrainka, so they were all arrested. Now the police will probably be on duty near all Ukrainian monuments.”

Now Anna “withdrew from all affairs” in the organization so as not to “harm the family”: “We used to be engaged in cultural and educational activities, and we saw many Russians who helped us, were with us on our [Ukrainian] public holidays. Now we can’t do anything: we just worry, we help our refugees. But you know how the authorities treat you, even if you help, you have to be careful.”

Now it is hard for her to live among the Russians, 90% of whom, as Anna read in the news, support the war. “When you start telling everything that happens [in Ukraine], you see aggression, people’s eyes are filled with blood, ready to eat you,” she says. “But there is a part [of Russians] that just sympathize, they come to me: ‘Tell us the truth, because apart from TV, we don’t see anything, we don’t know anything.’”

Anna does not believe that Ukrainians, when answering a question from the census about nationality, can hide their Ukrainian origin: “Everyone says:“ We are from Ukraine. We do not consider ourselves Russian. And we speak Ukrainian in the family. And there are many who are Ukrainian at home and Russian at work. They miss everyone from Ukraine; they all miss it. Even if they live here for 50 years, everyone wants to go home. They are all crying for Ukraine, and everyone is worried now.”

Anna thinks that after the end of the war, there will be no Ukrainians left in Russia. “I know very many who are waiting for the end of the war to leave here, because it is impossible to live here after what has been done there [in Ukraine]. I have a daughter in Chernihiv, how can I live here in peace? Anna asks. - I lived there for 40 years, worked at the school, my students, classmates, relatives are there, my parents' graves are there. The ‘liberators’ came and destroyed everything: in Chernihiv, 70% of the city is gone. How can I look at it? I just can't mentally live here. Morally live here. And then, maybe, physical reprisals will begin [against Ukrainians]. I do not exclude this.”