The Weekly Economic Update on Russia

Madi Kapparov, 17 July 2025

This week’s format is slightly different – it is a longer opinion piece with most critical news of the past few weeks contextualized for some simple analysis.

Nuanced Dekulakization and Selective Anticorruption Measures, Russia’s answer to Budget Deficits

Last week the Russian Ministry of Finance announced that the federal budget deficit had reached 3.7 trillion rubles for the first six months of the year, hitting levels planned for the entire year. Thus, the deficit is already at 1.7% of Russia’s annual GDP, a level planned for the entire FY2025 in a budget bill approved and signed into law by Putin only three weeks ago on June 24. The expanding budget deficit is driven by massive military spending estimated at 15.5 trillion rubles for 2025, shrinking export revenues especially in Oil & Gas translating to 8.7 trillion rubles in revenues for the federal budget in 2025, and lower than expected VAT collections at 7.0 trillion rubles for the first half of 2025. The consensus estimate by Russian economists for the FY2025 federal budget deficit is currently at 8 trillion rubles.

Also last week Russia observers were puzzled by the sudden alleged suicide of the newly-former Russian Minister of Transport, Roman Starovoyt, spawning a multitude of speculations. The flames of rumors were fanned by the confusion over Putin sending a wreath to Starovoyt’s funeral which was first reported by RIA but the propaganda agency later retracted. On the same day another senior official at Rosavtodor, Russia’s federal roads agency, died of an apparent heart attack. Starovoyt led Rosavtodor between 2012 and 2018. On June 19, Igor Petrov, deputy governor of Leningrad Oblast, was found dead allegedly killed by negligent discharge while cleaning a hunting rifle. The string of deaths of Russian government officials and senior executives started in 2022 even before the start of the full scale invasion of Ukraine, as analyzed by InformNapalm.

The deaths, however, should not be viewed as a curiosity or a special feature of the incumbent regime in the Kremlin. Given the positions of the deceased officials and managers, it is plausible to assume that some sudden expirations are part of the Kremlin’s selective anticorruption measures. Afterall, punitive measures against suspected and confirmed inefficiency, corruption, and dissent were dispensed generously in the 1930s and 1940s USSR. As part of the selective fight against corruption in the military and related industries, Andrei Belousov, an economist, replaced Sergei Shoigu. As a longtime Putin loyalist and his personal PR manager, Shoigu avoided serious repercussions for his failings and was relegated to the magnitudes less lucrative position of the Secretary of the Security Council where his role is reduced to being the Kremlin’s envoy to China and North Korea. Shoigu’s deputy at the MOD, Tumir Ivanov, was less lucky – on July 1 he was sentenced to 13 years on corruption charges.

However, loyalty to the Kremlin or even “friendly” relations with Putin do not always translate to personal safety or property rights protection. Anatoly Sobchak, the former mayor of St. Petersburg and the man responsible for putting Putin on the political map in post-Soviet Russia, succumbed to cardiac arrest in 2000 a month before Putin’s first elections. Some report that Sobchak’s two bodyguards showed signs of poisoning shortly after his death. In 2004 Roman Tsepov, Putin’s and Sobchak’s bodyguard during their St. Petersburg mayoral office days, was poisoned to death by a radioactive isotope (or leukemia medication). Both Sobchak and Tsepov were direct witnesses to Putin’s involvement in the extensive corruption schemes and drug trade the 90s St. Petersburg.

Boris Berezovsky and his associates also learned the hard way that Putin does not return favors. Berezovsky’s ORT TV (now Channel One in Russia) ran a compelling publicity campaign for Putin ahead of the 2000 presidential elections. Shortly after winning the election, Putin launched a series of reforms which Berezovsky allegedly opposed or was displeased with as he was not consulted beforehand. According to Yuri Felshtinsky, who at the time was in contact with Berezovsky, Berezovsky confronted Putin on the matter of the FSB being behind the 1999 apartment bombings. This potentially sealed Berezovsky’s fate. In fall of 2000, Berezovsky was charged with fraud and in 2001 his assets in Russia were seized by the government, forcing him and his associates to emigrate to the UK. In 2008, Badri Patarkatsishvili, Berezovsky’s close associate, died of a heart attack in the UK. In 2013, Berezovsky committed suicide in the UK (investigating coroner recorded an open verdict). In 2018, Nikolay Glushkov, another Berezovsky’s close associate, was strangled to death in London.

Now Russia is going through its third phase of great change over the past 35 years. And some Kremlin loyalists already learned that their loyalty came with no security guarantees. Vadim Moshkovich, the founder of one of the largest agricultural conglomerates in Russia Rusagro, was arrested on March 26, 2025 on the charges of fraud. Moshkovich despite having close connections to Dmitry Medvedev and Sergei Shoigu is now likely facing partial or full nationalization of his company. Rusagro was already partially nationalized. Some argue that Vyacheslav Volodin, the Chairman of the State Duma, is behind Moshkovich’s arrest with whom he came into conflict in 2018.

On June 25, 2025 Magomed-Sultan Magomedov was arrested on the charges of illegal privatization of Dagneftprodukt. Magomedov was until that point a member of the Kremlin’s local satrapy as a State Secretary of the Republic of Dagestan. On July 15 four subsidiaries of Caspetrolservice, formerly Dagneftprodukt, were nationalized. Assets of the nationalized subsidiaries include the largest refinery in Dagestan. Two of the subsidiaries were owned by Magomedov.

On July 5, 2025 another prominent Russian oligarch, Konstantin Strukov, was detained by the FSB attempting to flee the country on his private jet. Strukov, a longtime Putin supporter and a United Russia party member, was banned from leaving the country on July 2 after the Office of the Prosecutor General filed a lawsuit to nationalize Strukov’s Yuzhuralzoloto, one of the largest gold miners in Russia. The nationalization sparked a wave of concerned among the Russian elites prompting the Russian Finance Minister Siluanov to propose an alternative to nationalization – full state control over gold production by the company, a “soft” form of nationalization.

Moshkovich, Magomedov, and Strukov are only some nationalization examples of this year from a string of nationalizations which started in 2022. First nationalization victims were of foreign origin or foreign owned. However, until last week the Kremlin avoided nationalizing US-owned companies – Glavprodukt was nationalized on July 11. Since October 2024 Glavprodukt was placed under temporary state management. Glavprodukt’s ultimate beneficial owner is a Russia-born US citizen, Leonid Smirnov.

Some of the nationalizations since 2022 could be interpreted as mere redistribution of wealth in the style of the 1990s and 2000s. However, they also serve as a major source of revenue for the Russian federal budget, making the Office of the Prosecutor General another “tax collector” for the state. On July 9, 2025 Russian law firm NSP published a report estimating the value of assets nationalized or turned over to the state for temporary control over the last three years at 3.9 trillion rubles. Earlier in March, Novaya Gazeta estimated the value of assets owned by 411 companies seized by the Russian state at 2.56 trillion rubles.

Is this 21st century dekulakization sustainable and if so, how much in “nationalization reserves” does the Russian state have? The question has a political and an economic aspect. For our purposes we will only briefly discuss the political aspect and heavily simplify our economic analysis, as the ultimate goal is to arrive to a rough estimate of when the Russian economy can no longer sustain the invasion of Ukraine.

While Russia is an ethno-fascist dictatorship, the Kremlin still pays attention to public polls, especially focusing on Moscow, and must carefully balance interests of the many factions and clans within its political system. Vast majority of Russia’s population are not part of the ruling elite with 40% having no savings. I suspect that widespread nationalization would be either well received or ignored across Russia, especially in the poorer regions. It is part of the old “sovok” mentality. The situation in the imperial capital, Moscow, is more nuanced – many small and medium businesses and staff service the oligarchs. It is likely that those would not be pleased with the loss of their income, if their oligarch bosses fell victim to nationalization. However, the extreme opulence of the top 1% in Moscow has been upsetting the poorest Russians for years, and in 2017 1.1 million of Muscovites had incomes below the official subsistence minimum (~9% of Moscow’s population). However, if the nationalization is not well received by the masses in Moscow, the Kremlin has the largest contingent of the police (MVD) and Rosgvardiya in Moscow than in any other city in Russia. In 2016, there were 58,000 police officers and 27,000 Rosgvardia troops in the city, and now it is much higher.

Balancing interests of the factions within the political system is trickier. Thus, I went over the Forbes 100 Russia 2024 list ranked by net profit (no other Forbes ranking is available). The list is a proxy for all companies operating in Russia but obviously does not include every company in Russia that could be nationalized. I dropped companies with 10% or greater ownership by the Russian state (37 companies). This criterion eliminates many major political players who would not be directly affected by nationalization of the remaining companies. Of the remaining companies I identified the largest ultimate beneficial owner or group of owners. Of the 70+ names, by my subjective assessment the Kremlin would prefer not to nationalize companies owned by Alisher Usmanov, Vladimir Potanin, and Gennady Timchenko. However, I still included their companies in the estimation of the “nationalization reserve.”

However, before we move on to the numbers, let’s overview the stages through which the Russian economy went through and is yet to go through over the course of the war against Ukraine:

1. 2014-2022 lax Western sanctions and European demand for Russian oil and gas allowed Russia to accrue reserves in preparation for a full-scale war against Ukraine while sustaining a low-intensity conflict in Eastern Ukraine.

2. 2022-2025 government stimulus (war spending) and debt monetization (money printing) balanced the impact of sanctions. Some confuse debt monetization with “Russian style quantitative easing.” However, one must be very generous to equate Western style quantitative easing to the standard debt monetization being conducted in Russia. Without sanctions, the Russian government potentially could have kept the economy in this stage indefinitely.

3. 2025-20XX stimulus spending and debt monetization no longer generate growth. A mix of draconian measures will likely be implemented by the Kremlin to sustain the war in pursuit of their political objectives and at the expense of future growth and development. The end year of this stage depends on the extent and type of measures implemented.

The drastic cooling of the Russian economy this year does not indicate that the Kremlin would look to end war next year. In fact, many industries, such as coal mining, started showing strong signs of slowdown in 2024. In response the Kremlin boosted the rate of nationalization this year – the value of assets nationalized for the first six months of 2025 is nearly at the levels for the entire 2024. Moreover, on July 12, 2025 Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin signed a decree transferring property from the occupation administrations in the territories of Ukraine of Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, and Luhansk to the federal balance sheet. While this is not true nationalization (it is pure theft), those four territories are mostly not incorporated in Russian statistics and other reporting, so the move would still translate into revenue for the federal budget akin to nationalization.

Thus, the nationalization reserve will aid in estimating the end year of the final stage, 20XX. Thus, of the remaining 63 companies of Forbes 100 Russia, I approximate the nationalization value of each company to the book value of net assets (total assets minus total debt). While the real market value for many of these companies is much higher, in the absence of free markets realizing such value is impossible. Balance values of assets and debt were obtained from e-disclosure(.)ru, the Russian regulatory disclosure platform.

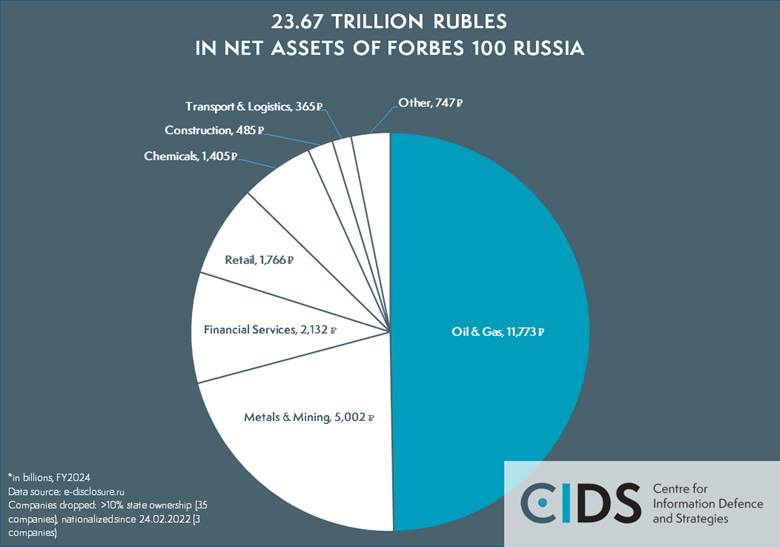

The total value of net assets for 63 companies with no state ownership for fiscal year 2024 was 23.67 trillion rubles:

The total value of cash and cash equivalents for 63 companies with no state ownership for fiscal year 2024 was 10.48 trillion rubles:

It is worth nothing an outlier among the 63 – Surgutneftegaz net assets for FY2024 were reported at 8.31 trillion with cash and cash equivalents estimated at 5.70 trillion rubles. The company has an opaque ownership structure.

However, the nationalization reserve is not the only source of funding for the federal budget deficit. Other sources that Russia has been tapping into:

1. The National Wealth Fund – for our purposes we will only use liquid reserves of NWF, most recently reported at 4.13 trillion rubles.

2. Gold reserves – entirely held in Russia and most recently valued at $249 billion or 19.43 trillion rubles at the official exchange rate at the time of writing (78.03 RUB/USD).

The current consensus estimate of the Russian federal budget deficit is 8 trillion rubles for 2025. Even if the entirety of the NWF liquid reserves is used, it would still leave 3.87 trillion rubles in unfunded deficit. For Q3 and Q4 2025, tax revenues from oil and gas are budgeted at approximately 4 trillion rubles. One of the ways to boost that is to devalue the ruble, as Russian oil export contracts are predominantly priced in the US dollar. So, to boost the 4 trillion to 7.87 trillion, the RUB/USD exchange rate needs to increase to 153.52 from the current 78.03. However, such devaluations were unpopular in Russia in the past as it continues to be a salient indicator of the state of economic affairs for an average Russian. Moreover, devaluations cannot be applied continuously.

I am aware of the generous simplifications that I am applying, and I will keep making them as this is not an academic paper. So, let’s assume the currently forecasted 2025 budget deficit of 8 trillion continues in consecutive years and all remains equal, including the sanctions. Also let’s assume that nationalized companies continue operating but result in no higher revenue for the federal budget – given that Russia has an effective corporate tax rate of 25-30%, this leaves ~70% slack in net profits for inefficiency of state management. And let’s extend the list of sources for funding for the deficit:

1. The NWF liquid reserves, 4.13 trillion rubles

2. Gold reserves, 19.43 trillion rubles

3. The nationalization reserve, 23.67 trillion rubles

4. Household savings, 57.30 trillion rubles.

Household savings held in current and savings accounts in Russian banks have long been speculated by Russian observers on Telegram to be tapped into by the state. However, such a drastic measure would require either sudden unannounced implementation to prevent bank runs or semicoercive convincing.

Consider a hypothetical scenario – later this year the Russian Central Bank drops the key rate to 10% which would likely translate to 8-9% interest rate on deposits offered by commercial banks. The Ministry of Finance concurrently starts issuing war bonds offering 11-12% coupon rate and sold to consumers for the principal amount. If the household savings conversion rate into war bonds is not the Kremlin’s satisfaction, they could forcibly convert via creative legislation, such as a mandated percentage of savings to be invested into war bonds.

The reduction in the key rate to 10% in the scenarios would be an entirely politically motivated move. The official inflation rate reported by Rosstat last week was at 0.79% vs. no more than 0.50% in all prior weeks this year. So, the official inflation rate picked up the pace again while the real inflation is likely higher. However, Nabiullina has been under increasing pressure for the past year or so to lower the key rate and to increase the target inflation rate from 4% to 7-8%, mostly recently by the head of CMASF Andrey Belousov. Moreover, Kremlin economists and State Duma deputies have been arguing for Soviet-style price controls (caps) for foodstuffs for months, and twice just last week. And Nabiullina’s economic rationale is unlikely to find more understanding in the Kremlin than the imperial ambitions.

NB: On July 16, the FT reported that a new submission to the International Criminal Court called for an investigations into Nabiullina’s and Siluanov’s role in the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine.

So how do the sources of deficit funding translate to 20XX, the end year of the final stage of the Russian war economy? Given the assumptions stated above, the best-case scenario is:

1. The NWF liquid reserves – used entirely in 2025

2. Gold reserves – partially liquidated in 2025 to fund the budget deficit, untapped in consecutive years

3. The nationalization reserve – untapped

4. Household savings – untapped.

This case Russia would have to scale back the war significantly already in 2026. The Russian military budget would have to be reduced by 8 trillion under our assumptions to balance the budget. I personally find this scenario to be very unlikely.

The realistic scenario is:

1. The NWF liquid reserves – used entirely in 2025

2. Gold reserves – partially liquidated in 2025 to fund the budget deficit, untapped in consecutive years

3. The nationalization reserve – the Kremlin manages to tap into half of the nationalization reserve translating to 11.84 trillion rubles

4. Household savings – the Kremlin manages to tap into a quarter of household savings translating to 14.33 trillion rubles.

Total funds available for deficit funding in this scenario are 26.2 trillion rubles. At a 8 trillion deficit annually, the Kremlin has 3.27 years putting the end of the third stage of the Russian war economy at Q2 2029. Again, after the funds are used up the Russian military budget would have to be reduced by 8 trillion under our assumptions to balance the budget.

The worst-case scenario is:

1. The NWF liquid reserves – used entirely in 2025

2. Gold reserves – the Kremlin liquidates half of the gold reserves translating to 9.71 trillion rubles.

3. The nationalization reserve – the Kremlin manages to tap into the entire reserve of 23.67 trillion rubles

4. Household savings – the Kremlin manages to tap into a half of household savings translating to 28.66 trillion rubles.

Total funds available for deficit funding in this scenario are 58.2 trillion rubles. At 8 trillion deficit annually, the Kremlin has 7.28 years putting the end of the third stage of the Russian war economy at Q2 2032. After the funds are used up, Russia must stop the war and arguably many other functions. This scenario is unlikely as it amounts to total destruction of the Russian economy.

The idea of this thought exercise is not to show “fortress Russia” but to bring attention to the necessity of supplying Ukraine with long range munitions letting the defender strike deep into the aggressor’s territory to *destroy* value. Afterall, a bombed-out oil well or factory has little to no value reducing the “nationalization reserve.”

Some side effects of nationalization that the Kremlin might consider beneficial

Russia continues to experience labor shortages. Estimates range from 1.5 million to 2.0 million. Last week the shortage prompted a regional government official to announce plans “to bring in” 1 million migrants from India. However, the Ministry of Labor later denied the existence of such plans. Nationalization nearly always introduces state mismanagement which would translate to lost jobs. While it is not always a one-to-one match between a job lost and job unfilled based on skills, it does reduce the pressure on the Kremlin at scale.

Moreover, Russia estimated that Russia spends 4 trillion rubles a year in salaries and bonuses for contract soldiers. A poorer population would be more eager to sign up with the military for lower salaries and bonuses.

The Kremlin’s perverse creativity cannot be underestimated. On July 8 the State Duma changed the criminal code introducing forced labor for up to 5 years. Only last week Rosstat reported unemployment at a new record low of 2.2%. Forced labor will be a punishment for economic crimes as well, including failure to pay wages for more than three months, falsification of financial statements, illegal formation and reorganization of a legal entity, illegal actions during bankruptcy, and violation of the requirement for mandatory repatriation of foreign exchange earnings.

Wages owed are growing across the board in Russia estimated at 1.5-2.5 billion rubles as of Q1 2025. Payroll taxes owed are also growing currently estimated at 352 billion rubles at the end of January-March 2025 period (double vs. last year).