Mar 27: Buying influence is really that simple

Led by Donkeys documentary, my comments and links to the Kremlin Playbook series

How to buy influence

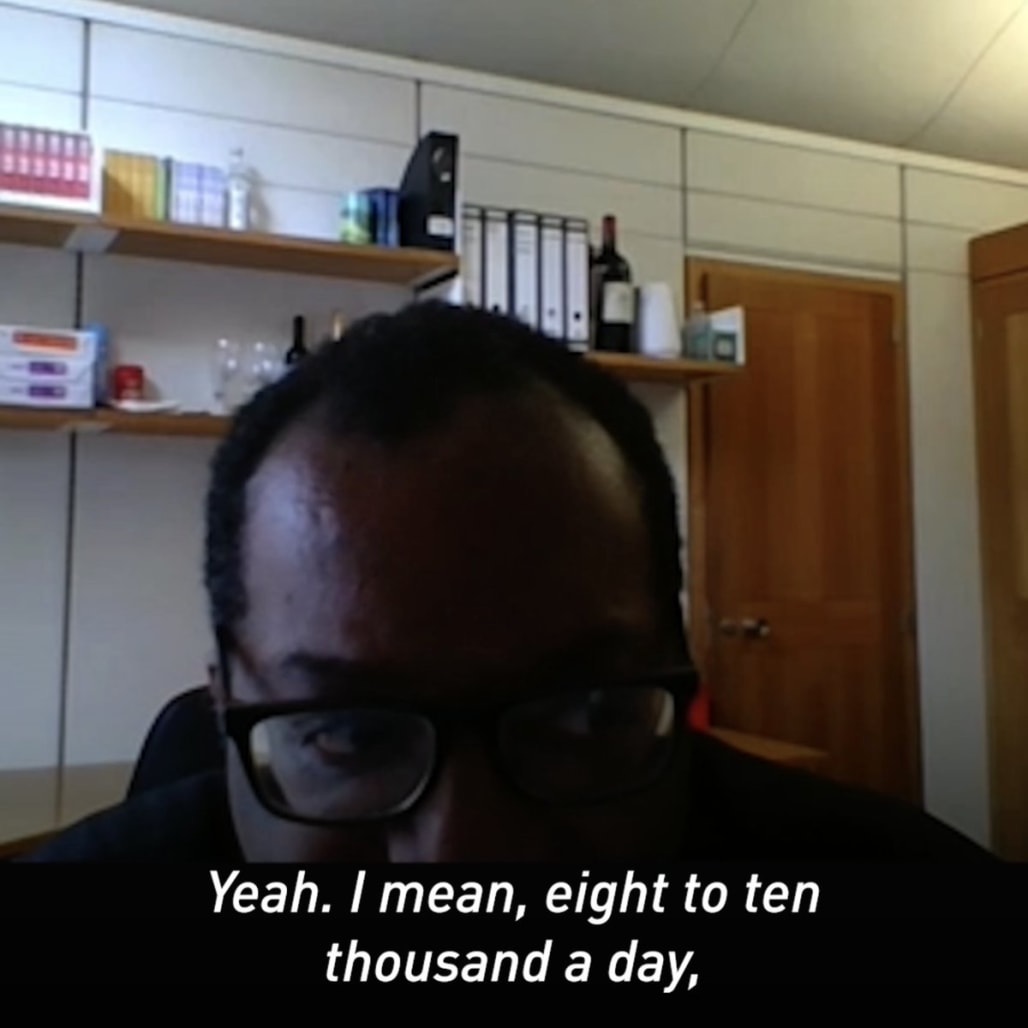

If you’re wondering exactly how malign state and non-state actors manage to buy the influence of our state representatives and stakeholders, then watch the investigative documentary by Led By Donkeys. It hasn’t been released yet but they’ve started posting teasers on their feed. They’re delicious.

They created a fake South Korean lobbying firm, which claimed to be hiring distinguished members of parliament in the UK. They did some research and found MPs who had expressed interest in financial affairs on their government webpages, so they contacted them by email, and invited them to a preliminary video meeting.

The trailers provide snippets of the video conference calls featuring three MPs who took the bait. Each MP expressed the amount of money they would charge to participate in future video calls, and trips to Europe and South Korea. One such MP is Matt Hancock, who served as Secretary of State for Health and Social Care from 9 July 2018 to 26 June 2021. He was the face of the Johnson government during the Covid pandemic crisis, covering up much of the mishandling of that government’s covid mitigation measures, and shady government procurement contracts. His spokesperson published this statement on Sunday:

He’s right: there’s nothing illegal going on here, and that’s the point. You can buy influence. Malign state and non-state actors will use this to their benefit. They take advantage of the loopholes in our system to weasel their way in. Italy is a stellar case. There is no legislation regulating lobbying or private foundations, which notoriously serve as vehicles to collect dark money for illicit dealings. Looks like the UK has the same problem when it comes to lobbying.

I was also shocked by the lack of security checks. The MPs in the video hadn’t done the minimun checks to verify the status of the the firm so what makes us think they’d check on anyone else. Their lack of attention to security could mean they end up working for a malign actor and providing access to policy-makers. Believe me, I see this online all the time. A snazzy bio profile on a website, stating that Mr Rossi is an anaylist, accompanied by a professional-looking but fake stock photo can go a long way with unassuming audiences. Most people don’t check to see if the people they are dealing with are real: a British member of parliament should.

This is the stuff of witting and unwitting agents of influence, which Russia and China have had so much success in recruiting over the years. Oleg Kalugin, former KGB agent in the United States, said that the Russians were able to recruit most of their spies in the United States by leveraging two main vulnerabilities: a thirst for money, and psychological weaknesses or addictions. We can add ego and ideology as motivators to the list as well, but the Russians were most successful with those who wanted cold hard cash to betray their countries. It’s a bit of a stretch to say that Matt Hancock is ready to sell state secrets to the South Koreans, but he could end up indirectly divulging sensitive information. Who’s going to check?

Malign state and non-state actors have been influencing our government representatives and institutional stakeholders for quite some time. I’m a little sensitive to this issue because Italy is a particular case. That said, there isn’t one Western democracy that hasn’t been touched by the temptations of a foreign power.

I’ve included links to readings from the Kremlin Playbook, authored by Heather Conley, president of the General Marshall Fund, and co-authored by other experts in the field. They’re very well-written and readable for a non-specialist audience. Led By Donkeys has touched on an issue that needs attention, and I look forward to the documentary once it’s released.

Further reading

Heather A. Conley , James Mina , Ruslan Stefanov , and Martin Vladimirov, Understanding Russian Influence in Central and Eastern Europe (Oct 13, 2016)

There was a deeply held assumption that, when the countries of Central and Eastern Europe joined NATO and the European Union in 2004, these countries would continue their positive democratic and economic transformation. Yet more than a decade later, the region has experienced a steady decline in democratic standards and governance practices at the same time that Russia’s economic engagement with the region expanded significantly. Regional political movements and figures have increasingly sought to align themselves with the Kremlin and with illiberalism. Central European governments have adopted ambiguous—if not outright pro-Russian—policy stances that have raised questions about their transatlantic orientation and produced tensions within Western institutions. Are these developments coincidental, or has the Kremlin sought deliberately to erode the region's democratic institutions through its influence to “break the internal coherence of the enemy system”?

The CSIS Europe Program, in partnership with the Bulgarian Center for the Study of Democracy, recently concluded a 16-month study to understand the nature of Russian influence in five case countries: Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Latvia, and Serbia. This research determined that Russia has cultivated an opaque web of economic and political patronage across the region that the Kremlin uses to influence and direct decisionmaking. This web resembles a network-flow model—or “unvirtuous circle”—which the Kremlin can use to influence (if not control) critical state institutions, bodies, and economies, as well as shape national policies and decisions that serve its interests while actively discrediting the Western liberal democratic system. The United States can no longer be indifferent to these negative developments, as all members of NATO and the European Union must collectively recognize that Russian influence is not just a domestic governance challenge but a national security threat.

Heather A. Conley , Donatienne Ruy , Ruslan Stefanov , and Martin Vladimirov, Kremlin Playbook 2 (2019)

"Foreign politicians talk about Russia’s interference in elections and referendums around the world. In fact, the matter is even more serious: Russia interferes in your brains, we change your conscience, and there is nothing you can do about it.”

– Vladislav Surkov, Adviser to Russian president Vladimir Putin¹

“Where Russia can work in darkness, Russian agents systematically exploit democratic institutions to acquire influence […] using corruption.”

– U.S. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI)²

The Kremlin has developed a pattern of malign influence across Europe. It does so through the cultivation of “an opaque network of patronage across the region that it uses to influence and direct decision-making.” ⁴ This network of political and economic connections—an “unvirtuous” cycle of influence—thrives on corruption and the exploitation of governance gaps in key markets and institutions. Ultimately, the aim is to weaken and destroy democratic systems from within.

There has been a visible political awakening to the national security threat posed by this widespread and insidious Russian malign influence since 2016. From the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act of 2017 to strengthened anti-money laundering rules in the European Union, the transatlantic community has taken some steps to address this threat. But to truly eradicate this threat, Western democracies must acknowledge their enablement of malign economic influence and uproot it from their financial systems.

Key Definitions

Enabler: One that enables another to achieve an end. Especially: one who enables another to persist in self-destructive behavior [. . .] by providing excuses or by making it possible to avoid the consequences of such behavior.⁵

Illicit financial flows: The World Bank defines illicit financial flows as “cross-border movement of capital associated with illegal activity or more explicitly, money that is illegally earned, transferred, or used that crosses borders.” This involves three main dynamics: (1) “the acts themselves are illegal (e.g., corruption, tax evasion)”; (2) “the funds are the results of illegal acts (e.g., smuggling and trafficking [. . .])”; (3) “the funds are used for illegal purposes (e.g., financing of organized crime).”

Money Laundering: Interpol defines money laundering as “any act or attempted act to conceal or disguise the identity of illegally obtained proceeds so that they appear to have originated from legitimate sources.

Donatienne Ruy , Heather A. Conley , Marlene Laruelle , Tengiz Pkhaladze , Elizabeth H. Prodromou , and Majda Ruge, Kremlin Playbook 3: Keeping the Faith (2022)

For six years, the Kremlin Playbook series has studied Russia’s malign influence efforts in Europe, primarily through the economic lens. This research showed the Kremlin has developed a pattern of malign economic influence in Europe through the cultivation of “an opaque network of patronage across the region that it uses to influence and direct decision-making.” The aim is to weaken democratic systems from within, using existing and creating new societal divides.

But what if Russia, for its own malign purposes, were to seek to influence religious or traditional views? The Kremlin Playbook 3: Keeping the Faith aims to protect these beliefs by exposing how Russian malign influence works in this particularly challenging and very personal dimension—a new strategic seam—to ensure citizens do not unwittingly become part of an influence operation. The instrumentalization of values, traditions, and religious beliefs is a relatively recent and particularly pernicious front of the Kremlin’s influence efforts in Europe and elsewhere. This study investigates these dynamics in four case study countries: Bosnia and Herzegovina, France, Georgia, and Greece.

This report explores how the United States and its European allies can protect the religious beliefs and values of their citizens from malign influence at a time when transatlantic societies are grappling with the speed of societal change. Societal anxiety and fear related to these rapid economic, demographic, and generational shifts—and the subsequent politics and political figures that seek to capitalize on them—have fueled societal divisions around the so-called cultural wars in Western societies. Through two main channels, the Orthodox world and the traditional values ecosystem, the Kremlin has taken advantage of these fears to accentuate societal wedges in Europe and Eurasia.