May 31: Bojan Pancevski, Did Merkel Pave the Way for the War in Ukraine?

As published in The Wall Street Journal on May 26, 2023

Did Merkel Pave the Way for the War in Ukraine?

The former German chancellor is unapologetic as critics reexamine her deals with Putin and reluctance to punish his previous aggressions.

By Bojan Pancevski, The Wall Street Journal, May 26, 2023

Dressed in an imperial purple blazer, Angela Merkel beamed at a ceremony in April as she received Germany’s highest honor, recognizing the achievements of her 16-year chancellorship. It was her first appearance on a live broadcast since leaving office more than a year ago. She was at peace with herself, she said. She now had time to indulge her long-standing interest in the Renaissance, and though politics had the reputation of being a “snake pit,” she added, she could recall joyful moments from her time in power.

For any other leader, receiving the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit at Berlin’s understated Bellevue Palace would have marked the crowning of a legacy. Only two other people had previously received the honor: Konrad Adenauer, the first post-World War II chancellor, and Helmut Kohl, Merkel’s own mentor.

But the award kicked off a controversy. Adenauer and Kohl would be remembered as great chancellors, said Wolfgang Schäuble, a member of Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union who twice served as a key minister in her governments. For Merkel, he said, “It’s too early.”

The ceremony belatedly jolted Germany into reappraising Merkel’s role in the years leading up to today’s European crises—and the verdict has not been positive. As Vladimir Putin wages a war of aggression in Ukraine, Merkel’s critics argue that the close ties she forged with Russia are partly responsible for today’s economic and political upheaval. Germany’s security policies over the past year have been, in many ways, a repudiation of her legacy. Earlier this month, Berlin announced a new $3 billion military aid package to support Ukraine in its fight against Russia, and an approaching NATO summit is expected to discuss how to include Ukraine in Europe’s security architecture—an extension of the alliance that Merkel consistently resisted.

Merkel was a key architect of the agreements that made the economies of Germany and its neighbors dependent on Russian energy imports. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has destroyed that strategic partnership, forcing Germany to find its oil and natural gas elsewhere at huge costs to business, government and households. Berlin was able to secure enough natural gas to carry its economy through last winter, but it is unclear how Germany will meet its long-term supply needs.

Merkel’s successive governments also squeezed defense budgets while boosting welfare spending. Lt. Gen. Alfons Mais, commander of the army, posted an emotional article on his LinkedIn profile on the day of the invasion, lamenting that Germany’s once-mighty military had been hollowed out to such an extent that it would be all but unable to protect the country in the event of a Russian attack.

Most controversially, former allies of Merkel and other experts say that her refusal to stop buying energy from Putin after he seized Crimea from Ukraine in 2014—she instead worked to double gas imports from Russia—emboldened him to finish the job eight years later.

At an event last year, Merkel recalled that after annexing Crimea, Putin had told her that he wanted to destroy the European Union. But she still forged ahead with plans to build the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, linking Germany directly to Siberia’s natural gas fields, in the face of protests from the U.S. Merkel’s government also approved the sale of Germany’s largest gas storage facilities to Russia’s state-controlled gas giant Gazprom.

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline was set to double Russian gas exports to Germany at a time when the country already depended on Putin for 55% of its gas supply. The pipeline was built but never came online, and it was later scrapped by Merkel’s successor because of the war in Ukraine.

Since leaving office, Merkel has defended the pipeline project as a purely commercial decision. She had to choose, she said, between importing cheap Russian gas or liquefied natural gas, which she said was a third more expensive.

After Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, then NATO secretary general, warned her against making Germany more dependent on a rogue Putin, who had just occupied and annexed part of a European nation. For Putin, he said, the pipeline “had nothing to do with business or the economy—it was a geopolitical weapon.”

Officials who served under Merkel, including Schäuble and Frank-Walter Steinmeier (her former foreign minister and now Germany’s federal president), have apologized or expressed regret for their roles in these decisions. They believe that Merkel’s policies empowered Putin without setting boundaries to his imperial ambitions.

Merkel, by contrast, has acknowledged no mistakes and offered no apology in interviews since leaving office. She declined to be interviewed for this article.

At the time her policies were made, they reflected the dominant view among German politicians and industrialists, who saw trade as the main source of growth for the German economy and did not think the country could interact just with Western-style democracies. Merkel has also spoken of her conviction that economic engagement with authoritarian countries could bring about a rapprochement.

Merkel didn’t react when Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky publicly invited her last April to visit Bucha, the site of alleged Russian war crimes, to see what he described as the results of her policy of concessions to Putin. Though she has condemned the invasion of Ukraine as barbaric, she also has urged negotiations with Putin.

In a speech last September, she said the late Chancellor Kohl would not only have supported Ukraine but ”would also think about what currently appears unthinkable, simply unimaginable—namely, how to develop something like relations with and to Russia again.” Delivered just as international organizations were launching investigations into Russian atrocities, the suggestion of rebuilding ties to Moscow struck some critics as, at the least, ill-timed.

Joachim Gauck, who was president of Germany when Putin first invaded Ukraine in 2014, said Merkel’s decision to boost energy imports from Russia in the wake of Putin’s aggression was clearly a mistake. “Some people recognize their mistakes earlier, and some later,” he said.

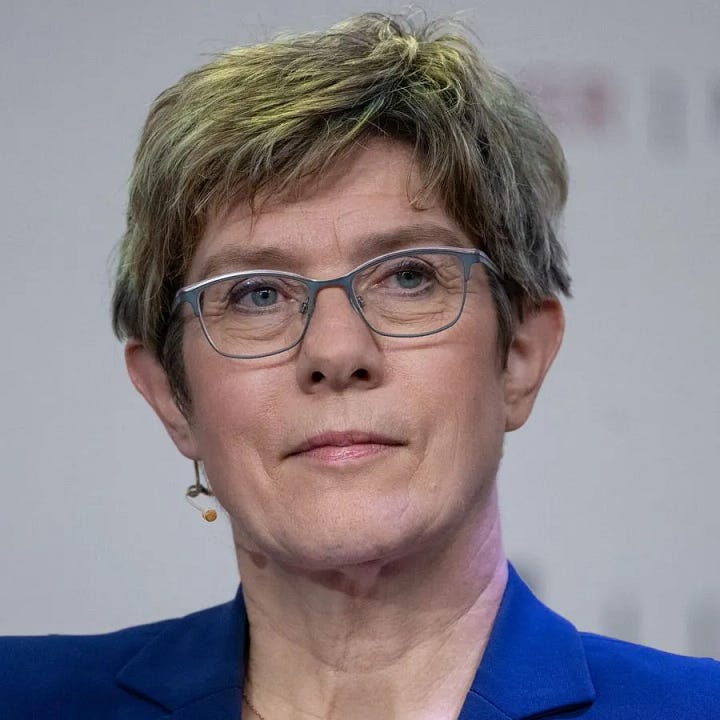

That mistake had its roots in another decision by Merkel: Her move to greatly accelerate Germany’s planned phasing out of nuclear energy in 2011, in response to the Fukushima disaster in Japan. The gap in energy supply created by this dramatic shift meant that Germany had to import more energy, and it had to do so as cheaply as possible. This meant becoming dependent on Russian natural gas, said Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, who served as defense minister under Merkel.

Kramp-Karrenbauer, once picked by Merkel as a possible successor, opposed Nord Stream 2 and tried in vain to rebuild Germany’s depleted armed forces. Her push to meet a NATO target of spending 2% of gross domestic product on defense, agreed upon after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, was blocked by the chancellery, Kramp-Karrenbauer said.

“We broke the promise to NATO, and I believe this was a big mistake,” Kramp-Karrenbauer said. “We abandoned the lessons of the Cold War. Diplomacy must be accompanied by military strength.”

Merkel’s role in shaping NATO policy toward Ukraine goes back to 2008, when she vetoed a push by the Bush administration to admit Ukraine and Georgia into the alliance, said Fiona Hill, a former National Security Council official and presidential adviser on Russia.

Merkel instead helped to broker NATO’s open but noncommittal invitation to Ukraine and Georgia, an outcome that Hill said was the “worst of all worlds” because it enraged Putin without giving the two countries any protection. Putin invaded Georgia in 2008 before marching into Ukraine.

After Putin first attacked Ukraine, Merkel led the effort to negotiate a quick settlement that disappointed Kyiv and imposed no substantial punishment on Russia for occupying its neighbor, Hill added. “No red lines were drawn for Putin,” she said. “Merkel took a calculated risk. It was a gambit, but ultimately it failed.”

Some observers believe that the failure to establish red lines and Germany’s continuing economic cooperation encouraged Putin to attempt a full-scale attack in 2022. “OK, so I could get away with that,” Putin concluded in 2014, according to Rasmussen. “So why not continue?”

Merkel still has supporters, and as Germany begins to grapple with her complicated legacy, many still hold a more nuanced view of her role in laying the groundwork for today’s crises.

Joe Kaeser, the former chief executive of the German conglomerate Siemens, worked closely with Merkel and accompanied her and other senior government figures on official travels, including to Russia, where his company was one of the largest foreign investors.

Kaeser, who now chairs the supervisory board of Siemens Energy, a listed subsidiary, agrees that Germany’s dependence on Russian natural gas grew under Merkel, but he says that there was—and is—no alternative for powering Europe’s industrial engine at a viable price.

“We didn’t expect that there would be war in Europe with the methods of the 20th century. This never featured in our thinking,” said Kaeser, who himself met Putin several times. He believes that Merkel’s Russia policy was justified. Even Germany’s new government has not found a sustainable and affordable replacement for Russian energy exports, he said, which could lead to deindustrialization.

Many defenders of Merkel say that she merely articulated a consensus. Making her country dependent on Washington for security, on Moscow for energy and on Beijing for trade (China became Germany’s biggest trade partner under her chancellorship) was what all of Germany’s political parties wanted at the time, said Constanze Stelzenmüller of the Brookings Institution.

“Without backing from the U.S.A., which was very restrained at the time, any tougher German reaction to the annexation of Crimea could hardly have been possible,” said Jürgen Osterhammer, a historian whose work on globalization and China has been cited by Merkel as an influence on her thinking.

For her part, Merkel is determined not to rely on historians for the historical record of her tenure. While unwinding from her long years of public service, she told German media, she is working on a memoir under a major publishing contract.

In retirement, Merkel told the German news magazine Der Spiegel, she has watched “Munich,” a Netflix movie about Prime Minister Neville’s Chamberlain’s infamous negotiations with Hitler in the run-up to World War II. Though Chamberlain’s name has become synonymous with the delusions of appeasement, the film offers a more nuanced picture of the British leader as a realist statesman working to postpone the inevitable conflict. That reinterpretation appealed to Merkel, the magazine reported.

She has also made an effort to rejuvenate relations with another retired statesman, President Barack Obama, whom she visited in Washington, D.C., last June. The former leaders enjoyed a museum visit and dinner at his favorite Italian restaurant. After the trip, Merkel complained that the growing criticism she is facing at home betrayed a lack of respect for her role as leader. “It is part of democracy to endure criticism, but my impression is that an American president who’s left office is being treated with greater respect by the public than a German chancellor,” she told Der Spiegel.

In April, Merkel was again asked on stage at a book fair whether she would not reconsider her refusal to admit having made some mistakes. “Frankly,” she responded, “I don’t know whether there would be satisfaction if I were to say something that I simply don’t think merely for the sake of admitting error.”

Bojan Pancevski is The Wall Street Journal’s Germany correspondent.