Olesya Khromeychuk, Ukraine fatigue’: why I’m fighting to stop the world forgetting us

By Olesya Khromeychuk as published in The Guardian on 25 January 2024

Before reading…

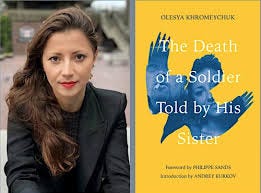

Olesya Khromeychuk is a Ukrainian historian and author, who lives in London. I had read Olesya’s book when it came out but I must say it was difficult to obtain, like many books written by Ukrainian authors. I ripped through it: please read it.

But the main reason for re-publishing her article below is not to sell books, and I think she would agree. Take your time to think over what she’s saying as it expresses truth and honesty about what Ukrainians are now living at home and abroad, and how we react to them. It hits home.

An Italian politician, Carlo Calenda, stood up in the Senate yesterday during the debate to explain the assurdity of our ‘Ukraine fatigue’, and the unconsciounable suggestion that Italy discontinue providing lethal aid to Ukraine.

“‘Italians are tired’. And this is something that we need to speak openly about.

I would like to understand what exactly Italians are tired of. They currently pay 1 euro per month so Ukraine can fight the war.

Are we tired of [paying] 1 euro per month? And how much does it cost Ukrainians to defend our peace?

Are we tired that the news interrupts Big Brother and X Factor with a piece about Ukraine?

What are we tired of? Because it’s difficult to understand exactly what we are tired of.

Calenda continues by underscoring that Ukrainians are tired of war, and of many other things—the death of their people and culture. To them the concept of ‘liberty’ is not some abstract notion. It’s a fact that each Ukrainian family has lost someone in the Holodomor and to this war. “Hearing that Italians are tired is an offence to Ukrainians,” he added.

I’ll leave you to read and think about Olesya’s thoughts.

‘Ukraine fatigue’: why I’m fighting to stop the world forgetting us

by Olesya Khromeychuk, The Guardian, 25 Jan 2024

Everyone likes to support an underdog, especially if it’s winning. But it’s one thing to win a battle, it’s quite another to win the war. And Ukraine cannot win without international support.

If you were 30% braver, what would you do to be a better ancestor?” the enthusiastic host asked a roomful of delegates in New York, gathered for a conference on democracy. “Take 60 seconds to think and share your answers in your small groups.”

My small group consisted of seasoned activists from different parts of the world. They were eager to discuss their opinions on courage and legacy. “I’d spend more time with my kids,” said one. “I would speak to people I disagree with more often,” said another. I kept quiet hoping no one would notice.

“You’re being quiet,” said one of them when everyone else had spoken. My group turned to me.

“Oh, I don’t know. It’s a difficult question.” I tried to get myself out of the trap. “I need more time to think about it.”

The thing is, I didn’t need time to think about it. As soon as the facilitator finished her question, my answer was right there, staring me in the face. Now that my small group was staring at me just as insistently, I couldn’t face sharing my thoughts with them. It seemed like I needed to be 30% braver just to utter the answer.

“If I were braver, to be a better ancestor, I’d join the army. The Ukrainian armed forces.”

At that moment, it was the only answer that rang true.

My response was met with the sort of uncomfortable silence I seem to bring to most social conversations. A friend has found a good term for that: a Ukrainian killjoy. It applies to those of us who keep talking about the war when people want to talk about their kids, the future and all those wonderful things that give us hope. Sometimes, we don’t even need to offer a digest of Russia’s recent bombardments, we end conversations just by entering the room.

When people think of Ukraine these days, they think of war, destruction, death, weapons, the need to produce and provide more weapons. Such thoughts bring little inspiration. And so, when asked to talk about Ukraine on international platforms, I am frequently encouraged to speak of peace, reconstruction and reconciliation. A relentless fight with no end in sight is a conversation killer. It’s also a reality in which most Ukrainians have been living since the start of the full-scale war.

Throughout history, Ukraine has been regarded as merely a buffer zone between Europe proper and the threat from the east. A stateless nation, it was denied a voice on international platforms for centuries. Despite successfully restoring its sovereignty in 1991, distrust persisted among states inclined to reserve decision-making seats exclusively for those deemed “great powers”, a designation that is frequently acquired through the imperialist oppression of other nations.

Ukraine experts have tried to shift the narrative to show the country as the gates of Europe, the crossroads of cultures, the bridge facilitating conversation among unlikely interlocutors in a multitude of tongues. For the outside world, however, Ukraine has remained a buffer zone lacking a clear identity – a territory that can be fought over, sacrificed or simply overlooked.

In 2022, after Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine offered the world a new narrative about itself: it was no longer perceived as a nation of leather-jacketed riffraff from the edge of Europe, ruled by dodgy oligarchs with large wallets and poor taste. It was a new incarnation of brave David unafraid of monstrous Goliath. The narrative caught on – because who doesn’t like a good remake of an old story?

For as long as they could, throughout 2022, Ukrainians kept this image up. After the liberation of the Kyiv region and the sinking of the Moskva, the flagship of Russia’s Black Sea fleet, the Ukrainian armed forces successfully freed the Kharkiv region and then proceeded to liberate Kherson. Each time, they uncovered mass graves, torture chambers, death and devastation. They were greeted by people whose gratitude for liberation was as great as the grief that had been brought by the occupiers.

The Ukrainian army was conducting successful campaigns, and countless observers the world over conveniently forgot that, back in February 2022, they had given this same army no more than a week. Fortune favours the brave, and so do the western partners. Success at the front persuaded even reluctant nations such as Germany to deliver assistance to Ukraine. Everyone likes to support an underdog, especially if it’s winning. But it’s one thing to win a battle (or several), it’s quite another to win the war.

Ukraine was never given enough support to win. The assistance it received was vital to survive, crucial to keep going, necessary not to lose. It wasn’t sufficient to win. It turned out that one thing that was truly in short supply was courage. Not that of the people of Ukraine – they had no choice but to be brave. It was the leaders of what is known as the free world who needed to be braver to put an end to this war. A real end. Not a temporary ceasefire, which territorial concessions might bring, not a stalemate in a war of attrition. The sort of end that could only come with Ukraine’s victory, which would include the restoration of territorial integrity violated by Russia in 2014 when it occupied Crimea, the dispensation of justice for the numerous crimes committed by the Russian troops and their leadership, and the provision of the type of security guarantees that would make a new wave of Russian aggression impossible.

For much of 2023, the eyes of the world were still on Ukraine, but this attention was that of a streaming TV addict, flicking through the fresh releases, looking for a new series to binge on. The release of the 2023 season of Russia’s war, branded as “Ukraine’s counteroffensive”, was delayed. And then something more gripping came along.

In early October, I was in Ukraine at the Lviv Book Forum, a literary festival. It was co-organised with the Hay festival, and thus attracted a good number of international journalists. On the morning of 7 October I met several of them rushing through the hotel lobby, bags packed, taxis waiting to take them back to the Polish border. They were off to the Middle East.

I started to get requests for comment from papers around the world, asking me to share how it felt to compete for attention with the Israel-Gaza war. I did not wish to partake in a competition of human suffering orchestrated by the media and exacerbated by our ever-shortening attention span. For people caught in the violence, be it in Palestine, Israel or Ukraine, this was no TV series. It was their lives on display: blood, sweat and tears. But I had to admit that the Ukraine fatigue we’d been afraid of since the start of the all-out war had descended in earnest. Outside the country, there was less and less investment in Ukraine’s victory.

“You need to change your tune, you know. People don’t take this victory rhetoric seriously any more,” said a man at a Christmas party, as 2023 drew to an end. I tried to convince myself he meant well.

“How should I fight this Ukraine fatigue here in London while my compatriots fight the Russian missiles at home?” I asked.

“I don’t know, but the whole victory thing isn’t working, because we’ve given you everything and you still haven’t won.”

I gasped for air and told him that we’ve also given everything and then some. I told him that earlier that night, just before heading out to the party, I had phoned my mother. She told me that a distant cousin who had been fighting at the front had been killed. She had spoken to our relatives who had been to his funeral.

“They only buried his legs, you know,” mum said on the phone. “Couldn’t find any other parts after the blast. His comrades recognised his legs because he had distinct tattoos.”

It’s good that I also have a tattoo, I thought. Who knows? Just in case. I didn’t say that to my mum. Instead, I said: “That’s awful. At least we could bury the whole of Volodya.”

Volodya, my brother, was killed in action in 2017. That was before the world discovered Ukraine. It was when leaders of the free world still shook Putin’s hand, bought Russian oil and enabled the aggressor to prepare for the inevitable escalation. My brother was killed in Luhansk region, near Popasna, when Popasna was still standing. Now, if you look at the aerial images of that city, you can see only ruins. Remnants of cities are like remnants of people, hard to recognise.

“I guess we were lucky. We didn’t need to look for tattoos to recognise Volodya’s body,” I said to my mum. She agreed. Ukrainian luck.

Not long ago, a friend of mine told me something she’d heard from a British acquaintance: “You don’t even realise how lucky you are to live in London!” My friend is from southern Ukraine, from a city that gets shelled almost daily. After months under Russian bombardment, she decided to leave a job she loved, her ageing parents, the life she’d been building in a city she adored, and seek refuge in the UK.

“Did they mean that you’re lucky to have escaped the war zone alive?” I ask her to clarify, although I suspect that that is not what they meant.

“No! They meant that I’m lucky because my host family lives in a posh bit of London, and I can enjoy all the opportunities that this city has to offer.”

Ah yes, those plentiful opportunities refugees enjoy. Like many displaced Ukrainians – not to mention refugees from other parts of the world – she struggles to make ends meet.

To cheer her up, I told her that, a couple of days earlier, a man sitting next to me at a conference dinner in a northern European capital had said to me: “Your life must be so exciting! Whizzing around the world, giving talks! Hundreds of people listening to you, wanting to know about Ukraine!”

She asked me if I told the guy to get lost. I didn’t. I told him that I’d rather have my brother alive and my homeland at peace than all this excitement. I’d rather people learned about my country in universities and bookshops. Although, in truth, that is not easy. There is still a gaping hole in university curriculums when it comes to the study of Ukraine. In Britain, there is a handful of places where Ukrainian history, politics and culture are taught, only two universities that have Ukrainian programmes and only one that offers a degree in Ukrainian Studies.

When it comes to bookshops, some now stock works on Ukraine, but the bulk of them are focused on the war rather than the country as a whole, and most are written by observers who are not ordinarily based in Ukraine. The voices from inside the country are not being promoted. And to add insult to injury, there are also bookshops that insist on shelving Ukrainian books in the “Russian literature” section. On my recent trip to Paris, I saw my book sitting uncomfortably among the Russian tomes, and insisted it be moved to a more appropriate place. The manager replied that he didn’t have enough Ukrainian books to create a Ukraine shelf. When I explained that the only connection my book had to Russia was that its protagonist had been killed by that country’s army, the manager responded that they didn’t think of the Russia shelf as relating to the country, but more as representing a region. And what region might that be: the Russian empire? The manager did not dignify me with an answer. He snapped the book out of the Russian shelf and shoved it on a temporary “new editions” table.

Perhaps rather than feeling enraged by the experience, however, I should have felt lucky: if it wasn’t for the war, my book might not have made it to the bookshops at all. There are countless blessings I remember each day. Here in London, I don’t have to hide in bomb shelters from Russian drones and missiles. I don’t have to spend the winter with no electricity like my fellow countrywomen and men do as Russia tries to freeze Ukraine into submission. Having said that, I start my day by checking the news and texting my loved ones in Ukraine to see if they made it through the night. Every day, I hear of another death of someone two handshakes away. On a bad day, it’s someone I knew or worked with, someone whose poetry I had been reading the day before.

My calendar is marked with morbid anniversaries: in 2024, Ukrainians commemorate two years since the full-scale invasion and 10 years since the start of the war. When I marked birthdays last year, I started by saying: “He would have turned 49; she would have been 38.” My grief is immense, as is that of all my compatriots: about 80% of Ukrainians know someone who was either killed or injured in this war. In this context, my fellow Europeans highlighting my good fortune is no more than a tiresome nuisance. I realise my luck. They are yet to acknowledge theirs.

‘Why don’t you join the Ukrainian army? You speak so passionately about your people’s fight and your brother’s service. Wouldn’t you want to join the ranks yourself?” The first time a journalist asked me this question was in front of a few hundred people at a literary festival. I felt a hot wave of blood rushing through my body and had to compose myself before I could answer. We had just been discussing my book about my brother’s death on the frontline. Did he really think that that was an appropriate question to ask? Didn’t he think that visiting one war grave is enough for one family? I searched for answers, but they were all flawed.

I don’t join up because I am not trained for army service; I have no useful skills to offer. But nor do many recruits who volunteered or were mobilised for service. I don’t join up because my contribution to the war effort is to write and speak to people all over the world to raise awareness about this war and galvanise support for Ukraine. But so could many Ukrainian writers, artists, poets and people of different professions who Russia’s invasion turned into soldiers. My gender is no reason to avoid service either. Thousands of women are fighting the external enemy and the internal obstacles put in front of them by the remnants of paternalistic culture. Why don’t I join up, indeed?

The answer I gave was true: I’m not in the Ukrainian armed forces simply because I am privileged not to have to join up. I live in London. I live in a state whose sky is protected by air defence and international alliances. Whose voice on the global stage is not doubted. The citizens of my adopted country, unlike those of my country of birth, are lucky not to have to be brave. Like them, I have the luxury of choice and I choose to be safe. For now.

This will be a year of choices. Billions of people in dozens of countries will go to the polls and exercise the right to make their voices heard. Of course, not every election serves as a genuine expression of people’s will, and there are also those nations where many either take their right to vote for granted because they never had to fight for it, or feel so disenfranchised that they don’t think their vote matters. In 2024, wherever we are in the world, we can’t afford to have our choices made for us. We are obliged to exercise our agency, however limited it might seem.

We have the power to elect political representatives who can enact changes that will outlast their time in office. We need to support politicians who view Russia’s war not as an inconvenience to their economies, but understand that tolerance of a warmongering state is what led us to this situation in the first place. We need to hold accountable those leaders who allowed Russia to enjoy impunity after 2014, who benefited from continued business with the aggressor country and thus contributed to the escalation in 2022.

Crucially, we must wake up from the slumber of inaction: this war is existential not only for Ukrainians; it is existential for those of us who want to live in a world governed not by brutal force, but by the rule of law. If we don’t win the fight for democracy in Ukraine, we’ll end up fighting for it closer to home. Let us then do all in our power to help Ukrainians win the fight not only for their freedom, but also for ours.

“For our freedom and yours” is a famous slogan in east-central Europe. It originates in 19th-century Poland, a state that had been partitioned by Russia, Prussia and Austria. The initial banner featured the inscription of this motto in Polish and Russian, highlighting the Polish anti-imperial insurrectionists’ support for the anti-Tsarist Decembrists’ revolt.

The Polish nation, which gave us the slogan, survived even when it was deprived of statehood. The striving for freedom lived on in exile, in the underground, and in the minds and hearts of people who willed their country back into existence after 123 years of statelessness. Poland was restored on the ruins of the imperial powers that had tried to destroy it. Like in the Polish case, the people of Ukraine managed to keep the flame of freedom burning even through the darkest times of Russian and Soviet imperialism. They wrote poetry in Ukrainian in prison cells and published it in underground press. They passed on a clear sense of identity to their youths, like a secret spell that was bound to work its magic sooner or later. Ukrainian statehood is hard-won.

The current existential fight requires the mobilisation of the whole of Ukrainian society, but victory also requires international solidarity. Ukrainians no longer have the privilege to choose whether to be 30% braver. That choice was taken away by Russia. They must be brave in order to survive. The rest of us still have that choice. We had better make it soon.

Follow the Long Read on X at @gdnlongread, listen to our podcasts here and sign up to the long read weekly email here.