For days we were waiting in the hopes that Victoria Amelina would recover from the injuries she sustained in the Russian missile attack at Kramatorsk on June 27. She did not recover. Victoria Amelina has died. Russian forces purposefully hit a well-known pizzeria where journalists and volunteers congregate. There is no strategic value in killing people enjoying an evening meal at a pizzeria in the company of their friends and family: It’s just pure terror and evil.

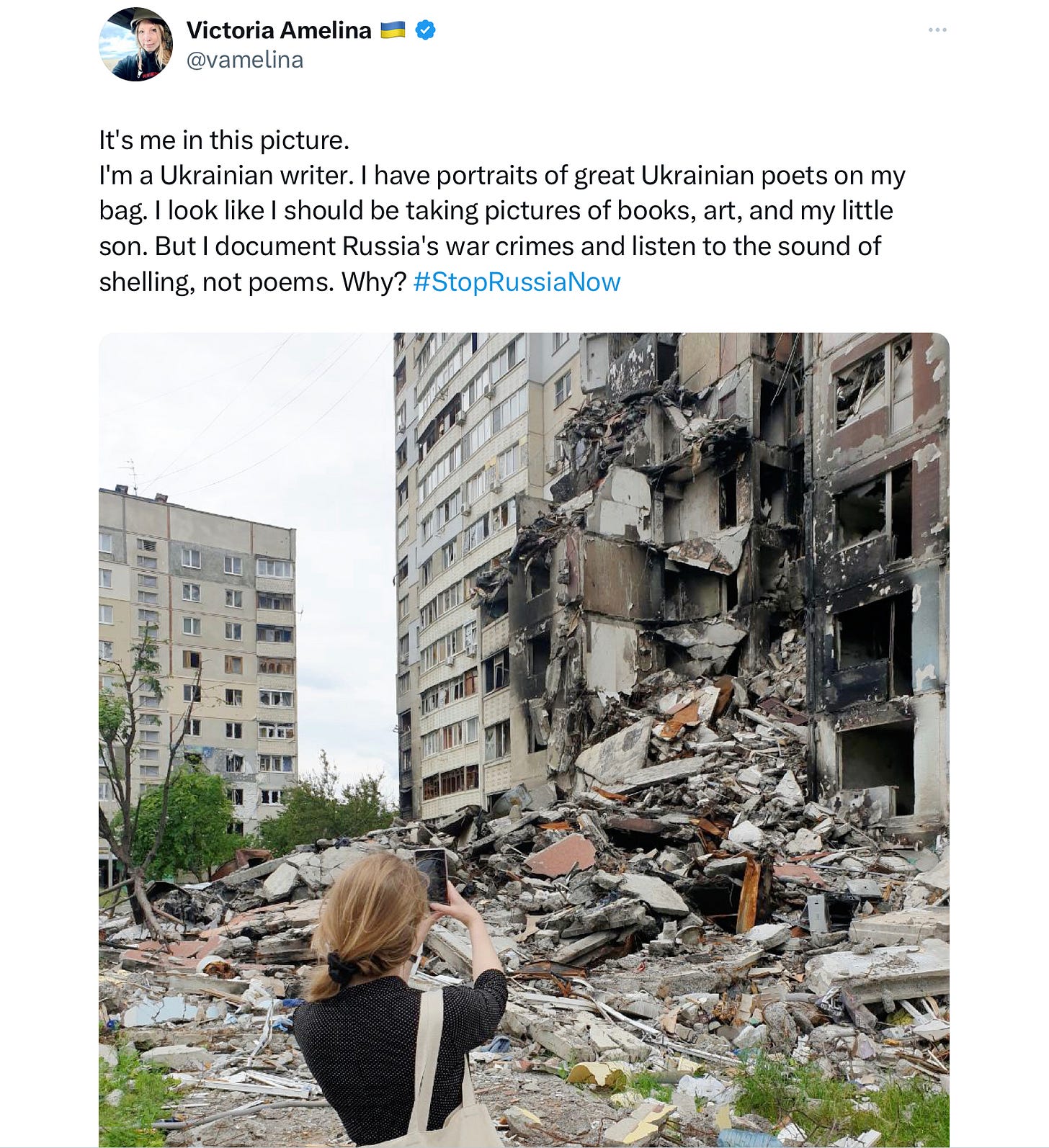

I discovered Amelina’s work when I was reading up on Ukrainian writers before Russia’s full-scale invasion, and then followed her efforts as she investigated Russian war crimes in Ukraine among her other activities. I’ve included her last instalment to Apofenie Magazine in the post below.

I didn’t know her personally, yet her death has hit me particularly hard because I respected her work, her determination, her courage. The pain expressed by Victoria’s close friends and colleagues is acute. Ariana Gic wrote about this loss and Ukraine’s collective daily losses in a thread below.

Military analysts, Ukrainian specialists and Russianists focus on the battleground—gains and losses, shaping operations, and offensive maneuvres. National security experts are debating whether Ukraine should or should not acceed to NATO. We have the luxury of discussing these issues from the comfort of our homes and workplaces, unimpeded by the threat or devastation of a Russian missile attack, or the daily violence of occupiers who have taken territory that is not theirs.

Ukrainian fighters, volunteers, and children die every single day at the hands of Russian violence and aggression. These precious souls cannot be replaced. Amelina is gone and cannot be replaced.

This is the truth that Ukrainians have expressed prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, and continue to tell us today: The war is an existential threat to their lives.

At this moment, I’m thinking of all my contacts, friends, and acquaintances and their families who are risking their lives in Ukraine. My only wish is that the allied leadership will provide all necessary means to defend Ukraine and end the war. They must take the economic measures necessary to bring Russia to its knees so it cannot be an existential threat to anyone in the future.

The more the war goes on, the more we will lose the friends we respect, and for Ukrainians, the family, friends and colleagues they deeply love.

In Autumn last year Victoria discovered notes of writer Volodymyr Vakulenko, killed by moscovians during Kharkiv region occupation. Volodymyr has hidden under the tree in the garden his notes of life during occupation before he was kidnapped and tortured.

For Victoria, for Volodymyr and thousands of Ukrainian civillian and military heroes we keep fighting their battle aimed to bring justice and punish the moscovian evil.

Victoria Amelina, Diary of Silence—Apofenie Magazine

Translated from the Ukrainian by Yulia Lyubka and Kate Tsurkan

Eight days before the great war.

My friend from Ivano-Frankivsk and I are sitting in a Lviv coffee shop with a young girl from the Donetsk region, to whom we were showing the city.

“Can you imagine,” says my friend, “my younger sister is being taught how to go down to the bomb shelter! In Ivano-Frankivsk! It’s madness!”

The girl from Donetsk region is silent, but I don’t let her remain so.

“Did you run for cover at school?”

“Yes, when there are three rings, then you have to run to the basement,” she answerscasually. “Because the siren is hard to hear there.”

Silence. Two days before the great war.

The Russians announce the recognition of the so-called people's republics in our Donetsk and Luhansk regions. I am finishing an application for a crowdfunding platform. In September 2022, we plan to hold our literary festival in a small town called New York, forty kilometers from Donetsk.. The application is called “The New York Literary Festival will be!”

I write on social networks that I’ve submitted the application in spite of everything, and I receive onlycheerful comments. No one writes to me anything like: “And we have already left Kyiv for Transcarpathia” or “And we have already crossed the border” or even “And I'm already in Mariupol with my brothers-in-arms.” Why didn’t we shout?

The first day of the great war.

“Better keep quiet,” a colleague writes to me publicly in a comment on social media. After all, I found myself abroad on the twenty-fourth; the war began two hours earlier than my plane was supposed to take off.

I do not face the first moments of the great war together with everyone, only with dozens of Ukrainians at the airport. They are silent – maintaining their dignity, as my acquaintance would advise them. Only a woman with a child in her arms is sobbing, wondering where to take her children.

Everyone else is silent.

On the same day, I find exorbitantly expensive tickets to Prague on the Internet.

The Czech border guard looks at my passport without a word.

She remains silent as she puts in the entry stamp.

And I cannot even thank her; something is caught in my throat.

The third day of war.

I’m back in Ukraine. The colleague who demanded that I keep quiet because I was abroad apologizes to me. I don't answer her. Maybe it wasn't such a bad idea to be silent during the war?

The fifth day of the war. I am meeting a friend at the Lviv railway station. We hug each other for a long time, silently.

The fourteenth day of war.

Friends who escaped from Bucha arrive. They have three children with them. One boy is silent the whole time. The Russians made him forget how to speak.

The twenty-first day of war.

The President announces that at 9:00 a.m., we would have a nationwide moment of silence for those who died as a result of Russia's armed aggression against Ukraine.

I’m surprised, since I remained silent for them for much longer than that. We will be silent for them not for minutes, but for years.

Since the start of the war, I have developed a cough – it chokes me as soon as I try to say something long and meaningful. Some say it's psychosomatic, while others say it’s because I sleep on the floor. Refugees sleep on the beds and sofas in my Lviv apartment (they say it's better to call them “new neighbors”, and that it's also better to keep quiet about the fact that they are refugees or IDPs).

Even when the sofa was later vacated (they went further west), I no longer wanted to sleep on it. I feel better on the floor – like those about whom I keep silent every day, even though they are still alive. It's a pity that they don't get any better from my coughing or my silence.

The fortieth day of the war. A friend tells me her friend was raped at a Russian checkpoint back in 2014.

My friend kept quiet about this story for eight years. Didn't we all already know what the occupation was?

The fifty-seventh day of war.

I remember that I promised to write an essay about the war. I am reading the testimony of a woman who escaped from Mariupol. She is a physical education teacher, and I am supposedly a famous writer. But I have nothing to add to her testimony.

I can only warn the reader that even she is silent about something — something unspeakable.

The fifty-ninth day of war.

I once again explain to my sister in Kherson why it isnecessary to evacuate from the occupied city, who is waiting for her in Kyiv and Lviv, what support would be available abroad, and so on. She writes back that she loves us all and asks me to stop convincing her asshe has decided to stay. In response, I send her an emoji saying “okay” in reply – that is, I remain silent. I don't know what to say to her anymore. I still ask her at times: “How are you?” But these questions and our falsely optimistic answers are just as good as silence.

The sixtieth day of war. Easter. "Christ is Risen!" I write in a message to the frontline. But he is silent. Silent.

I want to return to the time where teaching kids to go down to a bomb shelter is still considered crazy. But I can't remember what we were like then. And it is impossible to write about this war. I guess I should be quiet a little longer – one minute every day at 9 a.m. and for the rest of my life. Then I can tell you everything about war.

Ariana Gic: What Ukrainians have lost

Ukrainians are robbed of their homes, their schools, their hospitals, their grocery stores, their restaurants. Ukrainians are robbed of their rich and fertile soil, their food, their water supplies, and of clean air to breathe.

What are Russians robbed of? NOTHING.

Ukrainians are robbed of their mothers, their fathers, their brothers, their sisters, their sons, their daughters, their grandmothers, their grandfathers, their aunts, their uncles, their cousins, their friends, their colleagues, their teachers, their students.

Ukrainians mourn.

Ukrainians mourn. Ukrainians cry. They hide in bomb shelters. They hide in bath tubs. They hide in subways. Ukrainian children are stripped and robbed of their childhoods, filled with death, sadness, drones and missiles.

Ukrainians want peace. They want their sovereignty. They want their independence. They want freedom. They want democracy. They want to sleep uninterrupted and without fear of Russian missiles crashing down upon them in their beds.

What do Russians want? To keep waging an evil, genocidal war of extermination against the Ukrainian nation and people. To EXTERMINATE Ukrainians. To detonate nuclear hell on Ukrainians. To destroy Ukraine.

These Russians, who suffer nothing, who deserve nothing, have Western protection from the consequences of an evil & unimaginably vile war of terror, conquest, and destruction. Russians should not live in peace and tranquility as Ukrainians suffer at their hands.

Russians should feel every single consequence of waging illegal war upon peaceful people. Russians should not be protected from the consequences of genocide and war. They should be forced to accept the consequences of the hell of war. Perhaps then they'll stop destroying Ukraine.

Rose Horowitz, Victoria Amelina-Women to Follow

My friend Rose has been highlighting women to follow on social media: Victoria Amelina was a featured speaker in Rose’s Women to Follow Summit.

In this clip, Amelina says: "...I document war crimes because I believe justice is a foundation of democracy." Amelina’s sentiment is at the base of all Ukrainians defending their nation, their livelihoods, their people.

Victoria Amelina: Writers and War Crimes, Ukraine 242 Podcast

A conversation with Renowned Ukrainian author Victoria Amelina who has stopped writing novels. She says,“in 2022, it became impossible to write fiction (because) reality is so much more intense; it is impossible to invent stories anymore.” She now works as a war crimes researcher with the organization TRUTH HOUNDS.

In the Izium region, Victoria Amelina uncovered the war diary of fellow Ukrainian writer Volodymyr Vakulenko, who buried the diary before he was killed by the occupying forces. She found it with the aid of his father in the backyard of the family home.

Amelina now also keeps a journal of the work being done by war-crimes researchers and she has become a successful poet published by papers such as the New York Times, and various anthologies.

Victoria Amelina has been a celebrated Ukrainian author of novels and children's books since 2015, when she won several literary awards for her first book, The Fall Syndrome, about the events at Maidan in 2014. In 2017 her novel Doms Dream Kingdom was released and was shortlisted for the prestigious LitAkcent literary award and the European Union Prize for Literature in 2019. Amelina is a member of PEN International.

Very tragic and sad news this morning, such a wonderful talent doing priceless work. Rest in peace Victoria Amelina, gone but never forgotten.

Thank you for your reliable updates, always appreciated.✌️💙